In a context of information asymmetry between individuals and organisations, with the former often wary of the way in which companies and States use their personal data, innovation in services can quickly run up against a Gordian knot: how can personal data be used without weakening data protection or undermining user trust? It was this apparently intractable contradiction that the action research project led by the FING, in conjunction with a series of partners, set out to address.

Building the conditions for a positive-sum game

Taking inspiration from schools of thought such as VRM (Vendor Relationship Management) and the Quantified self, and from experiments carried out in the United States (Blue Button, Green Button) and the Great Britain (miData), MesInfos postulates that personal data can be a positive-sum game. If a company agrees to allow users full control and unfettered use of the data it collects about them while providing its services, users will not only trust the company in question (which may previously have lost their trust) but will also be in a position to reap benefits from using the data themselves. What is more, they will be able to share the data with other parties who may offer them new services.

From the individual’s point of view, the gains should be threefold. Having access to, and the possibility of reusing, data co-produced with the company would not only allow them to find out what the company knows about them, thus reducing information asymmetry, but also to avoid being subjected to inappropriate, unadequately personalized marketing, and to use the data for purposes directly aligned with their own needs and interests: to keep track of what they eat in order to keep an eye on their health, to consume in a manner more compatible with their values, to make better-informed life choices, etc. The gains for the company should be no less impressive: consumer trust would be strengthened without the need to wait for the introduction of a regulatory framework to protect the user; the data would be corrected and enriched by the user, and therefore be of better quality; sharing would give the firm feedback about its customers’ expectations; and finally, and most importantly, the circulation of data by and under the control of users could make it possible to invent (or co-invent with an ecosystem of third-party companies) innovative services that would boost user satisfaction.

A multi-stage research process

A panel of 320 volunteer testers was established. Each member of the panel had to be a customer of at least 2 of the partner companies.Involved in the project alongside Orange were three banks (Crédit coopératif, La Banque Postale and Societé Générale), one retailer (Les Mousquetaires) and one insurance firm (AXA). Orange shared its customers’ geolocation and communication data. These data were combined with information from till receipts, insurance contracts and bank accounts. 5 million structured data items were temporarily shared.

Each member of the panel was given access to their data, hosted via a personal cloud solution provided by the start-up CozyCloud. The Privowny service, which can be used to observe how information about us circulates on the web and to create a disposable email address, was also offered. The setting-up of this system, a long and complex process which took a year, revealed the extent to which the data-collecting companies were simply not technically or culturally ready to share those data with customers or users. The first lesson to be learned is that it will be impossible to pursue this approach without considerable efforts to standardise data based on inter-company, or even inter-sector, semantics, and without building metadata (the circulation rights attached to them, for instance).

Creativity still bridled

A competition was launched among a community of developers, designers and students, setting them the challenge of imagining and prototyping services based on cross-referenced user data.

Figure 1.

Orange formed a partnership with the Strate Ecole de Design, whose students played an active role in the experiment. The competition gave rise to around thirty service concepts and a dozen or so prototyped applications. MesInfos nutritionnelles [My Nutrition Info] was named the judges’ favourite. This nutrition coaching app allows users to track their consumption based on their food purchases, cross-referenced with open data from Open Food Facts.

Figure 2. The Tali concept

Tali was one of the three prizewinning service concepts. This compact smart object in the form of a pocket mirror offers the user living maps of their personal data (contacts, geolocation, calls, texts and emails sent).

The Orange prize was awarded to Mes1001choses, renamed QentCha, a mobile chat application which allows users to share geolocated information with their social network on a single map.

The competition was not able to offer participants alluring incentives: the data of the 320 panel members were destined to be destroyed at the end of the experiment and none of the partners envisaged opening up their data on an industrial scale in the short term. However, the competition did confirm – and this is the second lesson learned – that cross-referencing of personal data was a great source of service innovation, ranging from consumption to networking, from experience sharing, to self-knowledge, to comparing oneself with one’s social entourage.

Users cautious, but trust growing

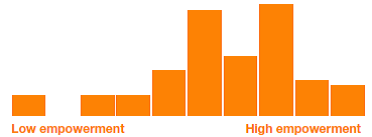

On the usage practices front, the company Eden Insight ran a discussion throughout the experiment and sent out 3 questionnaires to panel members before, during and at the end of the pilot scheme. All this was complemented by a focus group and a qualitative survey led by sociologist Eric Dagiral, which took the form of in-depth interviews with 8 testers. The first point worthy of note is that 67% of responses to the 3rd questionnaire gave positive feedback about the experience, with the respondents considering that MesInfos helped them to acquire new knowledge about the data and about themselves. 70% of testers indicated that they had gained in control and in their capacity to protect their personal data (customer empowerment) as a result of the experiment.

Breakdown of panel members by degree of empowerment

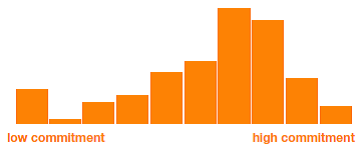

Another point that is interesting is that the level of trust felt towards companies in general did not vary between the start and end of the experiment, remaining middling (5.2/10). Conversely, the companies that took part in MesInfos are reaping the benefits of their involvement among testers. 80% of them now feel more committed to the partner firms (customer commitment), saying they feel more attached to the companies that gave them back their data, an act they see as proof of transparency.

“Customer commitment”: a commitment to partner firms

The survey also focused on those who used the platform little or not at all, in an effort to understand what was holding them back. The reasons given ranged from lack of interest or dissatisfaction when they tried the solution, (“boring applications”, etc.) to ideological rejection (“it goes against my values”), to aversion to technology (“I prefer to interact with people rather than machines”), to technical obstacles. “Privacy concern” (individuals’ concern about the use of their personal data and the impact it could have on their privacy) slightly at the end of the experiment, which could be explained by users’ newfound awareness of the sheer volume of data collected and its economic importance.

Nevertheless, qualitative interviews show that users did not experience any real “shock” when they discovered the data collected. When they did feel concerned, they were less worried about the company collecting the personal data than about third parties those data could be passed on to. Although it was little used, the Privowny service seems to have played a role in raising awareness of the extent to which personal data are transferred and re-used. The testers interviewed said that, in normal circumstances, they invest a lot of time and effort in documents that contain data (filing them, sorting them, etc.) and in the data themselves (checking them, particularly bank data). Thus the platform, which makes it simpler to access data in a single place, is of great interest to them. They also expressed a desire to be able to compare their data with other people’s (family, friends, a group) and to have grouped data about the family or the household alongside the individual information. Finally, they wondered about the capacity of this information about their everyday lives to help them know themselves better, and suggested that this objectivising knowledge might complement a more introspective personal approach.

Self-data: moving towards full-scale experimentation

Based on this initial experiment, a new season of MesInfos was launched in early 2015. The initial phase involves paying fresh attention to the various economic, cultural, technical and legal challenges posed by self data: identifying business models, securing buy-in from more than just pioneers, building a personal technical environment that is both reliable and easy to use, developing guidelines on conditions for circulation and the rights associated with data, etc.

During a second phase, a health and energy data hunting took place, paving the way for creative session providing new services.

In 2016, FING and its partners want to scale up the experimentation, involving the Grand Lyon local authority, and will join a European network of actors involved in self data.

More info:

To go further

The article draws on the findings of the various research reports.

- The MesInfos: http://mesinfos.fing.org

- Project VRM: http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/projectvrm/Main_Page

- CozyCloud: https://www.cozycloud.cc

- Privowny: https://privowny.com

- Blue Button: http://www.healthit.gov/patients-families/your-health-data and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Button

- Green Button : http://www.greenbuttondata.org/