"With profiles embedded in the service, customers with different needs will receive completely different services from the moment of installation."

New generation services are currently being developed at Orange Labs. The ideas that have been generated deserve to be shared in order to provoke reflection about the future ahead. One such new concept is a self-personalised service — a service that is aware of the user’s personality. This idea can both revolutionise the thinking behind customising services for users and open up new possibilities for creating services based on the Human-Centred Approach. Can personalisation benefit users? Can it be done while respecting privacy and data protection? Read on to find out.

In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandals and other data privacy and data misuse crises, data protection is a key hygiene priority. That is why data protection and privacy are the basic tenets of the Orange Labs research projects. This approach is called “privacy by design”. With privacy in mind, the overarching premise in Orange Labs is to create intelligent services that are closed ecosystems and do not depend on data in an external cloud. Further principles stem from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), which, in addition to ethical considerations, are key to creating modern technologies based on artificial intelligence. The world we create should be improved, and the technologies have to be safe. They are meant to be ethical in the best possible way. They are supposed to be beneficial for us, the users. They are meant to make our lives easier.

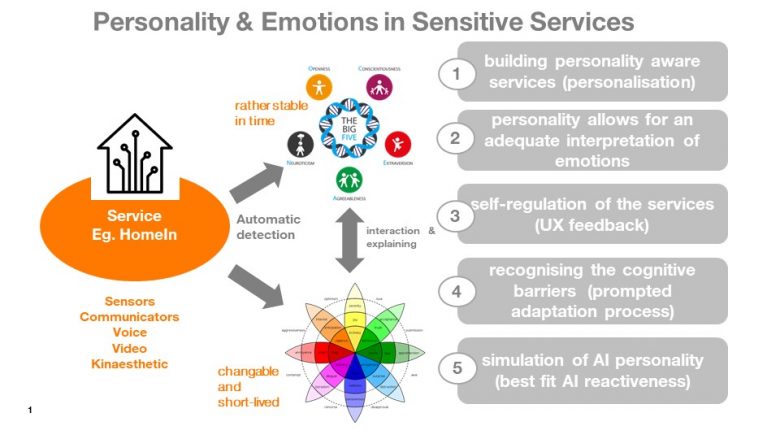

After a thorough review of scientific research, it was decided that the Big Five personality model would be used to describe users. The model is popular in psychology and is based on five independent temperamental dimensions.

- Extraversion: the intensity and amount of stimulation we need

- Openness to experience: how we react to new and unknown things

- Neuroticism or Stability: our stress tolerance

- Agreeableness: how we treat others

- Conscientiousness: how we organise our lives and define our goals.

One of the biggest influences in choosing this model was its high stability over time (temperament does not change quickly). These dimensions are related to the biology of our body and the properties of our nervous system (especially Extraversion and Stability).

In theory, the five dimensions are independent, but they are often related through associated behaviours. Let’s try to explain it. The more introverted someone is, the more stress they feel during public speaking. This stress will become more apparent the less someone can cope with emotional stress (neuroticism) and it will be less noticeable in people who are stable and additionally task-oriented, i.e. highly conscientious. In such a case, some features may multiply or eliminate the motivational effect of others. But be careful: this does not mean that such behaviour comes without cost. Public appearances are difficult for introverts even if it is not noticeable because of their emotional stability. In short, the Big Five is a dynamic motivation system. Personality motivations are certainly not the only things that determine our behaviour; they do however relate to the original nature of humankind and define the type of behaviour that people enjoy and seek out because of the satisfaction they get, or that they avoid due to the stress they feel. Extroverts are comfortable around people, very conscientious people love to plan and organise chaos, while open-minded people are happy and fulfilled when they are exploring.

Now we know what personality profiles are and the reasons for choosing the Big Five to describe users and their needs, let us consider how they can be used smartly for the benefit of the user. The goal was privacy-friendly and user-friendly profiling. But how can this be done? The idea is to insert a model or algorithm that profiles the user inside the service itself, for example a smartphone app. How does it work? The user installs the service and during installation, the service computes the personality profile based on the available data accessed by the user. The given profile is only available to the user’s application, ensuring that the data is protected and not visible to anyone else. This profiling will be an inherent part of the service installation, and it has many advantages: for example, the ability to fine-tune the initial interface configuration and feature presentation. Other advantages include the possibility of tailored support in the adaptation process and the simulation of matching chatbot or virtual agent personalities. Given that the application already knows the profile, it will be able to adjust the content and communication. It will also be possible to reduce users’ cognitive, communicative and technological barriers through a tailored adaptation process. Uncertainty and fears can be actively tamed and adapting to advanced technologies can be supported. Communication can be better adapted to users thanks to profiling.

How does it work in practice? Take a look at the image comparing two users—Peter Conscientious and Mark Chaos—of a smart calendar app equipped with a virtual assistant. As you can see, their names match their profile in terms of the conscientiousness dimension. Although it may seem strange, since calendars are a common tool, each user has completely different needs. Mr Conscientious loves the calendar and loves using it, and if we assume that he is also Highly Open, he can handle everything himself, including finding functions, learning about them and checking them in practice. Exploring makes him excited. He will make markers, charts, summaries and count the percentage of tasks completed on time. Mr Conscientious will do a lot, maybe too much, to satisfy his inner need to control everything. Meanwhile, Mr Chaos is adapted to a spontaneous life, has no plan, no intrinsic motivation to control his life or manage his time, but he also leads a busy life full of delays, missed deadlines and penalty interest. He needs help remembering, planning and recording appointments and commitments. A calendar with artificial intelligence would be advisable because a large part of the organisational work it is done for him. This is a simplification, but it illustrates how people can have different and conflicting needs based on their personalities.

Standard personalisation algorithms based on usage data from the service would have little chance of understanding Mr Chaos here as he hardly ever consults the calendar. As a result, he would get a lot of advanced functionalities that he would never use and the standard profiling mechanisms would not work. Some people may think that at least Mr Conscientious is happy with the common profiling. True and false. Don’t forget that he is also Highly Open to new experiences so there is a risk that the standard profiling algorithms would annoy him. And nothing will rile him more than a program that does everything he loves doing for him! Smart algorithms should make our lives easier, but in doing so, they should not deprive us of the activities we love doing.

What should we take away from this story? Technology will soon change the way we think about and design service creation. The “one-size-fits-all” model is no longer beneficial for all customers. The more common the service, the bigger the problem becomes. It is not possible to meet the needs of extreme personality groups at the same time. But thanks to smart technology and AI, there will be no need to look for a “golden mean” that will satisfy the majority. With personality profiles embedded in the service, customers with different needs will receive completely different services from the moment of installation.

If you want to know more:

- Allik, J., & McCrae, R. R. (2006). Erratum: Toward a geography of personality traits: Patterns of profiles across 36 cultures (Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology).

- Azucar, D., Marengo, D., & Settanni, M. (2018). Predicting the Big 5 personality traits from digital footprints on social media: A meta-analysis. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.018

- Back, M. D., Stopfer, J. M., Vazire, S., Gaddis, S., Schmukle, S. C., Egloff, B., & Gosling, S. D. (2010). Facebook profiles reflect actual personality, not self-idealization. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609360756

- De Raad, B. (2012). Structural models of personality, In The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511596544.011

- DeYoung, C. G. (2015). Cybernetic Big Five Theory. Journal of Research in Personality. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.07.004

- Frey, R. M., Xu, R., Ammendola, C., Moling, O., Giglio, G., & Ilic, A. (2017). Mobile recommendations based on interest prediction from consumer’s installed apps–insights from a large-scale field study. Information Systems, 71, 152–163.

- Gu, H., Wang, J., Wang, Z., Zhuang, B., & Su, F. (2018). Modeling of User Portrait Through Social Media, In Proceedings – IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICME.2018.8486595

- Hall C.S., C. J. B., Lindzey G. (2004). Theories of Personality, 4th Edition

- Hofstee, W. K. B. (1991). The Concepts of Personality and Temperament. In J. Strelau and A. Angleitner (Eds.), Explorations in Temperament: International Perspectives on Theory and Measurement (pp. 177–188). Boston, MA, Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0643-4\_12

- Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.797

- Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., & Graepel, T. (2013). Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(15), 5802–5805. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218772110

- Krzeminska, I. (2019). Data-Based User’s Personality in Personalizing Smart Services, 373 LNBIP

- Krzeminska, I., & Rzeznik, J. (2021). Personality-Based Lexical Diferences in Services Adaptation Process. Technium: Romanian Journal of Applied Sciences and Technology, 3(1), 61–73. Retrieved from https://techniumscience.com/index.php/technium/article/view/2101

- Matthews, G., Lin, J., Panganiban, A. R., & Long, M. D. (2020). Individual Differences in Trust in Autonomous Robots: Implications for Transparency. IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems. https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2019.2947592

- Matz, S. C., Kosinski, M., Nave, G., & Stillwell, D. J. (2017). Psychological targeting as an effective approach to digital mass persuasion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(48), 12714–12719. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710966114

- McCann, S. J. (2005). Longevity, big five personality factors, and health behaviors: Presidents from washington to nixon. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.139.3.273-288

- McCrae, R. R. (2002). Cross-Cultural Research on the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1038

- Robert, L. P. (2018). Personality in the human robot interaction literature: A review and brief critique, In Americas Conference on Information Systems 2018: Digital Disruption, AMCIS 2018

- Stead, H., & Bibby, P. A. (2017). Personality, fear of missing out and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Computers in Human Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.016

- Xu, R., Frey, R. M., & Ilic, A. (2016). Individual Differences and Mobile Service Adoption: An Empirical Analysis, In Proceedings – 2016 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Big Data Computing Service and Applications, BigDataService 2016, Institute of Electrical; Electronics Engineers Inc. https://doi.org/10.1109/BigDataService.2016.15