Pedometer use is part of the wider «Quantified Self» movement, which claims to help individuals to know themselves better by providing them with quantified data and promotes digital tools that track all kinds of physical and psychological states and personal activities. Its opponents argue that the promise of setting individuals free through self-knowledge, as well as the purported individual and collective benefits in terms of preventive healthcare, are illusory. They see digital tools as pointless gadgets, dangerous even, providing unreliable measurements and promoting anxiety-inducing self-monitoring practices that have counterproductive effects on health. The qualitative survey we conducted with 20 pedometer users (Fitbit, Jawbone, Withings, Garmin, Apple Health, Google Fit, Endomondo, etc.) looks at the facts underlying this debate through a detailed analysis of real usage practices.

A fairly active user base

Step counting seems a typical example of the «routinebuilding measurements» described in previous studies [1] and which serve to get users into good habits: in this case, encouraging them to walk in order to prevent sedentary lifestyles. It is not, in principle, a surveillance measurement to monitor a risk factor (such as excess weight), or a performance measurement to help monitor progress towards a goal (such as sporting performances). An examination of users’ motivations confirms this: most of them are simply hoping the tool will help them «walk enough». Monitoring of sporting activity (particularly running) and dieting are two classic contexts in which users begin counting their steps. Young people seeking to control the healthiness of their lifestyle (sleep, regular mealtimes, etc.) make up a third group of adopters. Regardless of the average number of steps they manage to clock up each week (4,000 to around 15,000), all those interviewed said they were satisfied with their use of the pedometer. A third are happy to see that they are able to walk more. They appreciate the congratulatory messages and the statuses rewarding their efforts, and like to set themselves challenges. 38-year-old Alexis said: «At the end of the day, if I’m at 9,800, I might summon up the courage to take the bins out to get my 10,000 steps in before midnight». Another third of those surveyed are happy to be able to check that they are walking enough: they appreciate having feedback on their number of steps, but do not need tools to motivate them. 25-year-old Marine said: «If I was less careful, I wouldn’t even have bought this wristband». The final third are happy to make walking part of their daily routine: having a steps target, even if they do not reach it, is a sign that they are taking care of themselves. 47-year-old Manu is reassured: «If people ask me if I do any sport, I’ll say no. If they ask me if I walk, I’ll say no. But this makes me realize that actually, I do! ». Our survey observes that, rather than generating anxiety-inducing practices, pedometers strengthen or consolidate self-esteem, without producing any miracle effect: quantitative studies support our finding that only around a third of pedometer users slightly increase their number of steps after adopting the tool [2]. The tools are «missing» their target somewhat, having been widely adopted by people who are already good walkers (those who have a non-sedentary job or who walk for pleasure).

A variety of usage paths

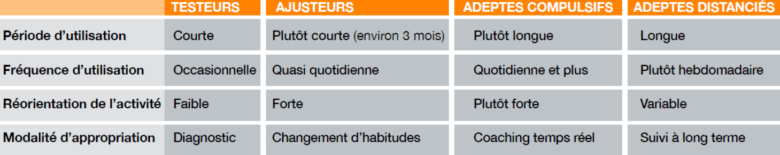

The table opposite summarizes the usage characteristics for each of the main usage paths observed. Abandoning pedometers after testing them and using tracking intermittently are just different ways of using the tools.

For those who have adopted tools in a lasting way, the step counts have now become a part of their walking activities, either through periodic reports (more detached enthusiasts), or through readings once or several times a day (compulsive enthusiasts). They often cite a hectic and unsettled lifestyle (lots of travel for work, lack of routine) as a reason why they need help to make sure they walk as much as they should. Without guidance, they find it difficult to meet their step targets. Their need for support from the tool is also linked to the gratification it provides: having the fact that they have reached their goal displayed causes them to feel more attached to their «coach». This taste for gratification is particularly pronounced among those who are also trying to stick to a diet. All of the enthusiasts interviewed say they went through a test phase prior to adopting the tool as a «support» in this way.

During the test period, users discover and get to grips with the tool: the number of steps they take per day is information they have never had beforeUsers measure journeys whose distances in miles or kilometres they do not know in terms of the number of steps they represent (home/work, workstation/canteen, etc.). They are surprised by the differences between workdays and weekends and between hikes and shopping sessions. Some remain «testers», not seeking to adjust their behaviour. Either their number of steps meets the tools’ default targets, or they consider that it is not necessary to meet this target, or they feel that they have neither the time nor the motivation.

For many of those interviewed, in contrast, there is a second adjustement phase. In this phase, users seek to readjust their behaviour in order to bring the measured value into line with their target. Adjusters are trying to find new points of reference, not by focusing solely on the measurements provided by their step counters, but in their everyday environment (getting off the bus earlier, no longer using the car to go to the bakery, using their lunch break to walk, etc.). They abandon the tools as soon as they have acquired these new points of reference. However, when they change jobs or experience a change in their family circumstances, they think about using a pedometer again to adjust their walking possibilities to their new living circumstances. For those who enthusiastically use the tools in a more sustained and continuous manner, the adjustment phase seems to go on forever. They remain on the lookout, always seeking to adjust their journeys on foot to their daily step target – virtually in real time, in the case of the most compulsive among them.

Intermittent use of activity trackers is a far cry from the life logging philosophy, but makes complete sense in its own terms. As far as the «adjusters» are concerned, intermittent use is a good thing, indicating that the tool is useful and efficient and it does not need to be used for a long time. Conversely, for «long-term enthusiasts» of the tools, abandoning them would mean abandoning their efforts to make sure they walk enough.

Measurements that cannot be compared

Routine-building measurements (number of steps, cigarettes, etc.) raise the question of the «right» target figure. The goal of 10,000 steps is perceived as coming from the WHO. This figure equates to 8 km a day, or an hour and a half’s walking. In reality, the institution recommends only 30 to 60 minutes of moderate activity 5 days a week in addition to normal activity. The gap between the two recommendations masks this «normal activity», which is not taken into account in the WHO target. The spread of tools has led the 10,000-steps-a-day target to gain currency in the public mind, despite the fact that it is questioned by experts [3] : all those interviewed agree that this is a good target. They find steps a useful unit of measurement and consider the 10,000 figure «achievable, but not too easy». Some, however, fall well short. «To be honest, it’s really hard! Over a week, I must do an average of 3,500 steps a day », admitted 47-yearold housewife Céline.

While the spread of pedometers has helped to spread the new standard of 10,000 steps, it has not regulated practices to any great extent. Indeed, each user has their own interpretation of what should count as steps and finds their own way of reconciling the activity they have done with the objective set in their interface.

Some convert various activities into steps (walking, running, cycling, clubbing, etc.), sometimes even entering values manually. Others count only their steps, but do so in two different ways. Some track all their steps from the moment they get up until they go to bed at night, while others only record their walking sessions. Thierry, a sporty 55-year-old and a keen walker, explains: «It’s like breathing. I don’t know if one day we will count the number of breaths we take per day». In contrast, 44-year-old Anne explains, «To my mind, the steps you do during the day to go to the photocopier and back aren’t really steps. I don’t count every single step I take in a day». In essence, she does not feel she has to have her smartphone with her at all times, but she takes it with her when she goes for a walk. In fact, even though the measurements taken by different individuals are all expressed as a number of steps, they are not at all comparable.

Users’ relationship with the 10,000-steps-a-day target also varies. Many accept big differences from day to day, particularly between weekdays and the weekend. Some keep the 10,000-step target in the interface, but set themselves a different target in their heads, adjusted to their situation. 25-year-old Jawbone user Marine, for instance, knows she is sporty and does several hours of dance a week. She explains: «I know that I very rarely reach the 10,000 mark. But I’m generally in the region of 6,000 – 7,000. And that’s enough for me, actually !».

Wellness: multiple targets, met in multiple ways

Pedometers are spreading a 10,000-step target which users do not dispute in principle. However, users’ practices do not align either with this standard or with one another. Each individual has their own way of counting and mentally adjusts their objective based on various parameters (constraints and priorities, overweight or not, etc.). Unless the whole family is equipped with the technology, pedometer use is an individual pursuit and, even though the data generated are not deemed to be particularly sensitive, they are not shared. These data help individuals to keep an eye on how healthy their lifestyles are, but they do so discreetly, away from prying eyes. Users accept the feedback their tools give them on their daily lives because these tools do not impose anything on them. «I’m the one in control,» claims 54-yearold Georges. In reality, this control is, in some respects, rather tenuous. Users do not know, for instance, where their data are stored or how they might be reused by third parties.

At a time when the market for these devices is moving towards a B-to-B model (health insurance and other insurance firms, corporate wellness), the fact that our interviewees did not appear concerned as to whether or not their data were circulated does not mean that they are willing to share those data. Unless users consent to such reuse, the measurements are likely to remain too singular to be comparable.

Furthermore, we have seen that use of the tools is driven more by selfesteem than by their actual effectiveness in bringing people into line with the 10,000-step target. The collective frameworks for use of the tools must avoid the adoption of inappropriate or stigmatizing targets which could result in loss of selfesteem. Finally, it should be underlined that intermittent, fragmented use of such tools is a widespread reality in today’s world. The figures provided by these tools are just one of the many elements we use to build our self-image and guide our actions. As such, they do not seem likely to take on a predominant role in shaping our behaviour.

Prospects…

Pedometers and other activity sensors are most commonly found on our smartphones, and this is probably the most visible part, for the general public, of the connection between the telecommunication and healthcare sectors. Orange is now working, through a consortium and partnerships with University Hospital Centers, on more targeted and reliable solutions around physical activity detection by sensors and, more generally, on sharing wellness and health data produced by the use of telephones. In this exploration, real technological innovations are under way, notably around the actimetry.

Focused on the sole use of pedometers, the study highlights wider adoption behaviors that oscillate between three attitudes: the use of these technologies for routine-building, surveillance and performance. In the light of these ways of using tools, we have to analyze the further innovations in health and wellness data analysis, risk detection, prevention and medical follow-up, by listening to the stakeholders and first and foremost the individuals described by these personal data. This seems a sine qua non condition for the most promising and responsible technical solutions to be successful.