“If you compare serious games with active teaching, they do not appear to be more effective in terms of learning, whereas on average they are more expensive.”

In recent decades, games have been used as a model for designing various schemes, including teaching. “Gamification”, the application of game-design elements in non-game situations, has arisen as part of the popularisation of video gaming since the 1990s. Gamification promises the same in all fields: It is based on the idea that a game is inherently more attractive, more immersive and more captivating than other human activities.

Education was the first field to use games for non-entertainment purposes, doing so since at least the 19th century. Since 1820, the École Supérieure de Commerce in Paris has carried out “simulated trading”, which consists of putting its students in the position of traders, competing one against the other. Modern business schools still do this. The educational game sector has been developed in many contexts, including vocational training, since the 1980s. It targets adult audiences in particular, via what are now known as “serious games”. Serious games are games that are designed with the explicit purpose of transmitting knowledge or skills. For this reason, they radically differ from mainstream video games, although these can also encourage learning. As a key telecommunications player, as well as a large company, Orange encounters these games and the discussions that surround them, both as part of work on digital education and when training its employees.

This article reviews scientific studies on the effectiveness of these serious games and, in particular, the five most up-to-date state-of-the-art meta-analyses on the issue when conducting the study in 2018 (Vogel et al., 2006; Sitzmann, 2011; Girard, Ecalle and Magnan, 2012; Wouters et al., 2013; and Clark, Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth, 2016). The meta-analysis technique consists of aggregating data from a multitude of published studies in order to arrive at more robust conclusions than each of the studies when taken separately. In particular, it allows us to measure the effect of study conditions on results. The general conclusion of these studies, widely used by the media as well as by practitioners, is that games are more effective than traditional forms of teaching. However, this outcome should be put in perspective. Serious games are more effective than traditional teaching but they do not produce better results than more active forms of knowledge transmission and are often more costly to implement.

Games and learning

Some theorists believe that games are better for learning than school. James Paul Gee (2003) criticises schooling for being too abstract and centred on theoretical content, far removed from reality. In his view, video games offer an alternative pedagogical model, based on the primacy of practice, the learner’s direct experience and feedback loops that allow learning by trial and error. Mark Prensky (2008) stresses the importance of learner motivation. According to him, school motivates mainly through sanctions, positives (reward) and negatives (bad marks). The learning activity is not motivating in itself — instead motivation stems from its consequences. In contrast, the purpose of a game is self-evident. Playing the game is a goal in itself. In short, a game is thought to have the ability to turn unattractive activities into things that are done for pleasure.

More fundamentally, these authors argue that the very model of a game is closer to what contemporary knowledge about education considers effective teaching (Gee, 2003). This literature demonstrates that learning is first and foremost gleaned from experience and the generalisation of particular cases. Some experiences are particularly conducive to learning, such as those that are “structured by specific objectives”, “need to be interpreted”, provide “immediate feedback”, provide “the opportunity to apply lessons learnt from past experiences” and allow interaction (Gee, 2003). Indeed, learning means recording typical situations, storing them in your memory and drawing reusable principles of action from them. And it appears that video games, or at least some of them, fulfil these conditions. They offer objectives, the aim of the game, and provide immediate validation in the form of points, winning or losing.

From this perspective, failures are learning opportunities. It is by losing that we test the limits of the game’s world and learn the right way to do things. However, the concern with video games is that failure is less risky than in real life. One can simply start the game again. These games are structured by the accumulation of experiences. Each level, each part, builds on what has been learnt in previous levels, and the vast majority of games increase in difficulty as the player progresses, increasing the possibilities for action whilst the player continues to learn how to perform basic actions. Finally, players are explicitly encouraged to reflect. They must analyse past actions, often collectively in player communities. In this sense, games, as with school, teach content. However, games do so through practice, while school, according to its critics, seeks to do so in an abstract way.

Figure 1: Interface of the serious game, Mecagenius (Potier, 2016)

Measuring the effects of games

The theory predicts that serious games will have a beneficial effect on learning. What is the reality? Many studies, of varying quality, have been conducted on this issue. The “effectiveness” of teaching is measured by a knowledge differential, a learner must know more after teaching than before. Above all, to demonstrate the effectiveness of serious games, a learner using them must know more than a learner who does not use them. In practice, these measurements are taken through pre- and post-learning questionnaires.

In general, the meta-analyses indicate that serious games improve learning. We learn more, on average, in situations where they are used rather than in situations where they are not used (Clark, Tanner-Smith and Killingsworth, 2016). If only these global conclusions are considered, the effectiveness of serious games appears to be demonstrated. However, this result must be put in perspective. First of all, the studies analysed are of very unequal quality. Furthermore, it appears that the most robust studies in methodology are also the least conclusive. The strictest meta-analysis, which only includes randomised controlled trials(1), concludes that there is no evidence of the effectiveness of serious games (Girard, Ecalle and Magnan, 2012), and the likelihood of finding a positive result is greater in lower-quality studies (Wouters et al., 2013).

Moreover, even studies that show the positive effect of serious games on learning do not identify any effects on learner motivation (Wouters et al., 2013). So, if serious games are beneficial, it is not, as the theory predicts, because they constitute a motivational activity in themselves. It seems that the reason is more related to the active side of things. The game is effective because it is a learning context that promotes action.

Moreover, the positive effect of serious games only appears under certain conditions. Contrary to what one might think, the aesthetic quality of the game is not a determining factor, nor is its “entertainment value”, that is, its resemblance to commercial games (Sitzmann, 2011). What’s more, games that seek to immerse the player in an enveloping and coherent environment, like those that players prefer in their usual gaming, are less effective than simpler games.

Above all, the effectiveness of games depends heavily on the learning context. Games are only effective if they are controlled by the learner, not by the teacher, and only if they are accompanied by other teaching techniques. Game-based teaching sessions that exclude any other method are less effective than traditional teaching (Sitzmann, 2011). Finally, games must be practised over time. Isolated game sessions are not effective and it is only when learners have unlimited access to the game, including out of class, that the results are best (Wouters et al., 2013). This being said, games do not have the “magic” power to teach new knowledge quicker, but they are based, like traditional teaching, on repetition.

Perhaps the most significant outcome of this research is that the effectiveness of serious games depends largely on the learning situation to which it is compared. Effectively, serious games seem to prove themselves when compared to a lecture. However, when compared to active teaching, such as tutorials, role plays etc., there is no difference, and sometimes other methods even outperform them. In short, it is less the game itself than the active nature of teaching it implements that is effective. This is more generally in line with current thinking in educational science.

Work or play?

Beyond the general effectiveness of the method, how does it actually work? A number of theoretical texts have criticised serious games as not being real games. For example, classic definitions of a game emphasise the absence of real-world consequences. However, serious games transgress this property. They are certainly not the only type of game to do so (e.g. with gambling the consequences are also real), but it does make them controversial. For some, it is a simple coating, the appearance of a game that does not fool players.

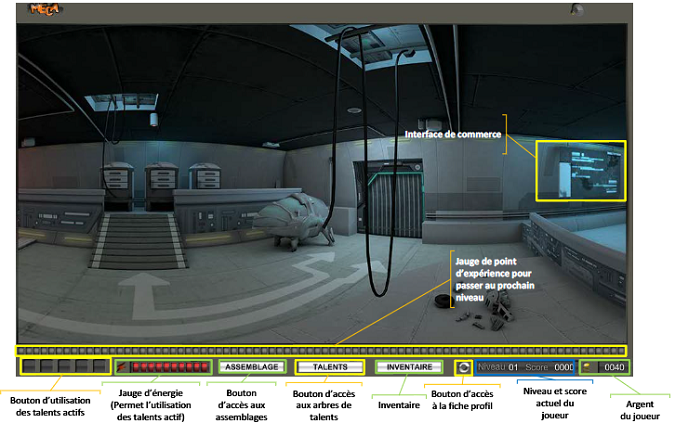

Figure 2: The serious game, SimLead (Martin, 2017)

The few qualitative studies on the subject demonstrate this ambiguity. For participants, serious games are rarely experienced as a game because the consequences are known to be real. For example, Lydia Martin has studied the use of a helicopter flight simulation in professional training for members of management in a large company. Players adapt under the watchful eye of their managers and supervisors, approaching the experience like an exam (Martin, 2017).

Moreover, participants face great inequality in the situation. In Martin’s study, only one of the participants managed to adopt the detached attitude that the designers of the training wanted to promote through the game. This participant was also the only one in this group who played board games regularly as a hobby. Experience is therefore the key to adaptation in this case (Martin, 2017).

Conclusion: Are serious games really needed?

So the widespread idea that serious games are the future of learning needs to be moderated. They certainly appear more effective than traditional teaching. But on the one hand, whilst this result still merits support, the best studies fail to replicate it. Whilst on the other hand, and above all, the key factor here is less the game than the activity, and alternative active teaching methods seem equally effective. When globally considering training materials, these findings are significant. Serious games have high development costs and their design requires rare skills. Caution should be exercised when considering them instead of alternatives. In most contexts, other teaching methods are just as useful as and easier to implement than serious games. Research in educational science also encourages further reflection on learning techniques with particular attention paid to the context of their implementation.

Footnote

1. This method consists of randomly dividing the subjects of an experiment into several distinct groups, subject to different experimental conditions, in order to measure the specific effect of these conditions, exclusive of selection bias. It is considered as standard protocol in experimental medical and social sciences.

Bibliography

• Clark, Douglas B., Emily E. Tanner-Smith, et Stephen S. Killingsworth. 2016. « Digital Games, Design, and Learning. A systematic meta-analysis ». Review of Educational Research 86 (1): 79-122.

• Gee, James Paul, What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

• Girard, Coralie, Jean Ecalle, et Annie Magnan. 2012. « Serious games as new educational tools: how effective are they? A meta-analysis of recent studies ». Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 29 (3): 207 19.

• Martin Lydia, « Entraves à l’attitude ludique avec un jeu sérieux intégré dans une formation managériale. Un exercice plus qu’un jeu? » Sciences du jeu 7, 2017.

• Potier, Victor, « ‘Soyons sérieux et jouons un peu !’ Navigation aux frontières de la classe par le jeu vidéo d’apprentissage Mecagenius », Sciences du jeu, 5, 2016.

• Prensky, Mark, Digital game-based learning. Paragon House Publishers, 2008.

• Sitzmann, Traci. 2011. « A meta-analytic examination of the instructional effectiveness of computer-based simulation games ». Personnel Psychology 64: 489-528.

• Vogel, Jennifer L., David S. Vogel, Jan Cannon- Bowers, Clint A. Bowers, Kathryn Muse, et Michelle Wright. 2006. « Computer gaming and interactive simulations for learning. A meta-analysis ». Journal of educational computing research 34 (3): 229-43.

• Wouters, Pieter, Christof van Nimwegen, Herre van Oostendorp, et Erik D. van der Spek. 2013. « A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. » Journal of Educational Psychology 105 (2): 249-65.