Africa is currently experiencing an unprecedented digital boom. Orange, a major player in this digital transformation, invests heavily in emerging countries, developing innovative services and participating in research programmes and pilot projects, particularly in connection with sustainable development objectives (financial inclusion, education, health, etc.).

This article provides an overview of the financial practices of informal sector entrepreneurs in sub-Saharan Africa. What are their main financing methods? Which institutions do they apply to? How do the entrepreneurs use mobile money services? Does mobile money pave the way for innovative forms of business financing and investment?

The results presented in this article are part of a collaborative project involving Orange researchers and the “Les Afriques dans le monde” (LAM) laboratory (LAM – CNRS – Sciences Po Bordeaux) aimed at gaining a better understanding of digital uses in the informal sector and their impact on business dynamics, as well as their economic performance. A first survey conducted in Dakar resulted in collection of a large body of data from a representative sample of 500 informal sector entrepreneurs (1); this data is used in this article.

Limited use of banking and poorly distributed banking services

In Dakar, slightly less than one in two informal sector entrepreneurs have a bank account, whether at a bank, a cooperative institution or a microfinance institution (MFI). The rate of use of banking services varies depending on the profile of the entrepreneur and the characteristics of their business. It is higher among the most qualified entrepreneurs, as well as among older and female entrepreneurs. The higher use of the banking system by women may be surprising, as it contradicts what appears in academic literature. A more detailed analysis of the Dakar context would shed light on this observation (the special role of women in money management? actions targeted towards women encouraging them to use the banking system?). The rate of use of banking services is also higher among businesses with the highest turnover, those that employ staff, those with actual work premises, those that conduct trade activities and those undergoing formalisation procedures. However, no difference was observed based on the age of the business activity.

In addition, having a bank account does not necessarily mean that the banking services usually offered by financial institutions are used. Indeed, less than half of informal sector entrepreneurs with bank accounts said that they have previously applied for credit, only one third have a credit card and less than one in ten use online banking services.

Getting credit from banking institutions seems far from being customary among entrepreneurs with bank accounts. Although almost half say that they have previously applied for credit, and few have been rejected, the percentage of business activities under credit is low. Another sign of this limited use of the banking sector is that almost none of the respondents cite bank credit as the main source of financing for the launch of their businesses. We can therefore question the outcome of these credit applications. Did most entrepreneurs change their minds, turning to other financing methods or deferring spending? Did they take out small bank loans? Did they take them out for purposes other than to launch the business activity or investment (to ensure working capital)? If credit was taken out, once repaid, it seems that entrepreneurs do not automatically commit to new loans.

As for entrepreneurs without bank accounts, a reluctance towards bank credit also seems to be felt. Most entrepreneurs not using banking services remain unconvinced of the usefulness of bank accounts. When asked why they are not using banking services, a large majority say they do not need it for their business, compared with those mentioning the high cost of the services offered. Lack of confidence in banks is also cited by three in ten entrepreneurs, while almost two in ten think that the bank would not open an account for them.

Mobile money: room for improvement for professional use

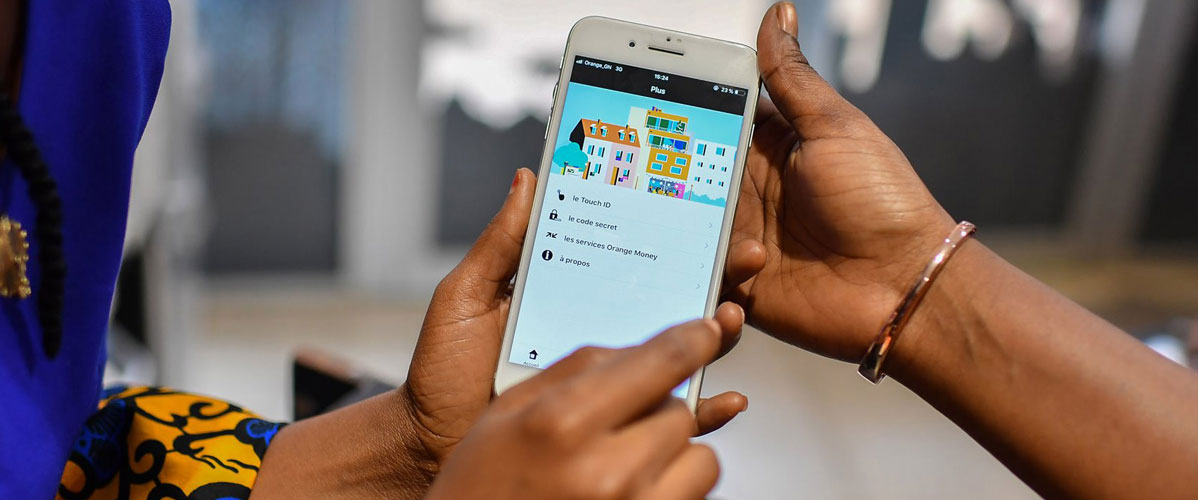

Launched for the first time in 2007 in Kenya by the operator Safaricom, a subsidiary of Vodafone, mobile money spread to West Africa in 2008 thanks especially to Orange, which launched its Orange Money service for the first time in Ivory Coast, and to Wari, which was founded the same year in Dakar. Today, mobile money covers a large part of the Senegalese population, with almost all of Dakar’s informal sector entrepreneurs adopting it.

Although personal use is widespread among informal sector entrepreneurs, the spread of its use for professional purposes leaves considerable room for improvement, with only around six in ten entrepreneurs using it so. In addition, the frequency of use for professional purposes remains limited for most entrepreneurs: Only four in ten say they use it professionally several times a week.

In addition, the use of mobile money for professional purposes is more widespread and marked among informal sector entrepreneurs with bank accounts. Seven out of ten use it for professional purposes compared with less than half among entrepreneurs without bank accounts. The difference is just as significant if we only look at regular users: a third of entrepreneurs with bank accounts use it several times a week compared with only a little more than one in ten among those without bank accounts.

Having a bank account, the use of mobile money on a professional basis is more widespread among the most qualified entrepreneurs, as well as for business activities generating the most turnover, those that employ staff, those that have actual work premises, those that conduct trade activities, those involved production activities, and those undergoing formalisation procedures. No difference is observed based on the age of the business activity, and, unlike banking, the use of mobile money does not vary with age or sex.

The use of mobile money for transferring money locally is widespread, while international money transfer concerns just over a quarter of transfers. Bill payment by mobile money is as common as buying telephone units (more than half of professional mobile money users do this), while four in ten use mobile money to set aside money.

In summary, there are five profiles of use of financial services among informal sector entrepreneurs

From the information available in the survey, we established a typology of informal sector entrepreneurs based on their use of banking services and mobile money (2). Five profiles emerged.

The most represented profile is that of “diversified users”, which includes almost a third of informal sector entrepreneurs. These are regular and diversified users of both banking services and mobile money. Among them, the most educated entrepreneurs (secondary school level and above) are largely over-represented, as are the business activities generating the most turnover, employing staff, having actual work premises, conducting trade or involved in production activities. Digital usages are the most developed.

“Mobile money centric users” only use mobile money. They do not have bank accounts, but use mobile money in personal and professional contexts. This category covers around a quarter of Dakar’s informal sector entrepreneurs and their socio-professional characteristics, as well as those of their business activities; they are not particularly noteworthy, except for over-representation of men and the production sector.

Unlike “mobile money centric users”, “bank centric users”, who represent slightly more than one in ten entrepreneurs, have bank accounts but do not use mobile money for professional purposes. This profile is also not especially noteworthy, except that there is over-representation of service activities.

“Ordinary users” only use mobile money, just for personal use. This profile is widespread among the entrepreneurs surveyed (around a quarter of them). Among them, the following are over-represented: entrepreneurs with a low level of education, one-person businesses, those providing services, those with no actual work premises and those that generate a low turnover. Among them, we mainly find the figure of the small informal sector business for survival.

Finally, the least represented profile, only anecdotal, is that of “non-users”, entrepreneurs who use neither mobile money nor banking services. They have a profile similar to “ordinary users”, but there is also an over-representation of men and those under 30 years of age. This is the category that is least equipped with smartphones.

Thus, the proportion of each of the profiles varies based on the business sector. While “diversified users” are over-represented in trade and production activities, the least developed financial profiles are over-represented in the sale and processing of food as well as in services.

The distribution of these profiles also varies depending on turnover. The proportion of profiles with little or no use of financial services decreases as turnover increases, while the proportion of diversified users increases. Likewise, profiles with little or no users of financial services are the majority among entrepreneurs working alone, while the proportion of diversified users increases with the size of the business.

Finally, the diversity of financial usages is strongly linked to equipment and digital usages. As a result, diversified users of financial services are over-represented among smartphone owners and even more so among regular Internet users.

Conclusion

The analyses carried out on data from the LAM survey in Dakar in 2017 confirm the low distribution of traditional banking services among informal sector entrepreneurs. Less than half of them have an account with a bank and/or microfinance institution. More importantly, having a bank account does not guarantee access to the financial services generally associated with banks. This finding allows significant room for emerging financing and credit services backed by mobile money, which is rapidly spreading in sub-Saharan Africa. While telecom operators are developing credit offerings in partnership with financial institutions, will they be able to support the financing needs of informal sector businesses? This depends on the attractiveness of the offerings and how they meet the needs of business financing and investments (which generally relate to higher amounts than the “picocredit” and microcredit offerings of the operators). Equally, this requires better understanding, beyond the channels of access to finance, which, in the economic, social and institutional context of the informal sector economy, means that an entrepreneur considers financing and investment as a means to continue and grow their business activity. These questions will be at the heart of doctoral work that will soon be carried out at Orange.

(2) The typology was obtained by implementing a multiple factor analysis to balance the weight of the variables relating to the use of banking services and that of the variables relating to the use of mobile money for professional purposes. An ascending hierarchical classification on the first two factors from the factor analysis revealed the five profiles. Details concerning the construction of this typology can be obtained from the authors.

Learn more

“Mon mobile, mon marché. Usages du téléphone mobile et performances économiques dans le secteur informel dakarois” (My mobile, my market: mobile phone use and economic performance in the Dakar informal sector), Réseaux, 2020/1 (No. 219), https://www.cairn.info/revue-reseaux-2020-1-page-105.htm

Orange/LAM survey

Survey conducted in the Dakar region in 2017 from a sample of 500 unregistered physical production units and/or units without formal accounting, representative of the population of informal sector entrepreneurs based on quota criteria (gender, geographic and sectoral distribution). For practical and operational reasons, the fixed and visible units of the Dakar region were investigated, except for agricultural, animal, forestry and fishing activities. Economic activities like street trading, which do not have a fixed location, are therefore excluded from our analysis.