Since 2014, Orange has been working to transform the African agricultural sector by offering various digital services dedicated to producers with the aim of improving their incomes, increasing their productivity and better positioning them in the agricultural value chain. These include, for example, consulting services, marketplace services or farm management services.

Digital technologies could also be leveraged for carbon farming in Africa.

Carbon farming is emerging as a response to climate and agricultural challenges, and represents a significant development opportunity for Africa.

What is carbon farming?

In contrast to intensive agriculture, which depletes soil and reduces its ability to sequester carbon, carbon farming is an agricultural system based on a set of practices from conservation agriculture that reduces CO2 emissions while increasing carbon sequestration in the soil.

To restore soil vitality and, beyond that, its function as a carbon sink, a regenerative or conservation approach to agriculture must be encouraged. This also leads to other benefits, such as better water quality and greater protection of biodiversity. Our goal of achieving better production while minimising our environmental impact is based on the following three pillars: no-till farming (using techniques that do not involve ploughing), permanent cover (no bare soil, introducing intermediate crops or intercropping) and crop rotation (no monocultures). There is also a fourth pillar around knowledge: It is an approach that requires supporting producers to facilitate them in acquiring new practices and it is the role of agricultural experts and advisors to work closely to make this change management succeed in the field.

The expected benefits of carbon farming for African producers

On the African continent, agriculture accounts for more than half of jobs and 15% of GDP. Mainly driven by small producers, it faces immense challenges: climate change, land degradation, limited access to finance. The Soil Initiative for Africa, led by the African Union, aims to reverse the trend and restore the health of agricultural land.

According to the publication “Carbon farming in Africa: Opportunities and challenges for engaging smallholder farmers”, paying small producers for agroecological practices is a powerful tool. This model of Payment for Environmental Services (PES), based on the carbon market, would make it possible to reconcile the fight against global warming with rural development. Compensating African producers for their environmentally friendly practices could be a key factor in scaling up efforts to combat climate change, while also enabling them to economically develop their agricultural activities.

Involving small producers in carbon farming has several advantages:

- On the one hand, it can improve the efficiency of their operations, reduce their production costs, open up higher value-added markets and provide them with additional income through the resale of carbon credits. A recent study by the Boston Consulting Group[1] shows, in a fairly concrete way, that this agricultural model is economically viable. Even though this analysis was conducted in Europe, it is reasonable to assume that this result can be applied to the African continent.

- On the other hand, and concomitantly, this type of practice is entirely positive for the environment and society: Healthy soil, better water quality and reduced greenhouse gas emissions make it possible to imagine a scenario with better living conditions for all living beings on the planet. A virtuous circle can then be envisaged.

Principles of carbon compensation

The economic activities of many companies emit carbon. Different policies are being pursued to reduce them, but a certain portion remains unavoidable. The idea is to do what is called carbon offsetting through a trading system. For this purpose, international rules have been established, which were included in the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The concept of emissions rights has been defined, allowing rich countries to purchase emission reductions from developing countries through a carbon credit principle. It should be made clear that this contribution does not cancel the company’s carbon impact.

Initially, a regulated carbon market was set up for the most polluting companies. They have a carbon emission quota: They can sell any unused portion of their quota on this market to companies that have exceeded theirs. In 2000, the UNFCCC[2] created a voluntary carbon market that is open to all businesses and individuals. They can voluntarily contribute to certified carbon sequestration projects through carbon credit trading. The cost of credit (per tonne of CO2 equivalent) is linked to several factors: It will depend on the type of project, its location, certification label, supply and demand etc.

At COP 21 in 2015, the Paris Agreement[3] established two new carbon markets (Article 6 of the treaty): The first is a bilateral agreement between two countries; the second is an exchange between countries and private companies.

Unfortunately, the carbon credit market has been plagued by numerous cases of malpractice, and the image associated with this principle of offsetting has been greatly tarnished. At COP 26 in 2021 (Glasgow), a decision was made to create a Supervisory Body[4] (Article 6.4) whose task is to develop and supervise the requirements and processes to make the carbon credit mechanism operational and reliable. At COP 29, the recommendations[5] made by this UN entity were adopted, in the hope that this would bring new momentum to what was a highly afflicted market between 2021 and 2023. Each carbon credit will be associated with a single centralised registry to avoid double counting and the environmental performance of projects will be audited reliably and independently[6].

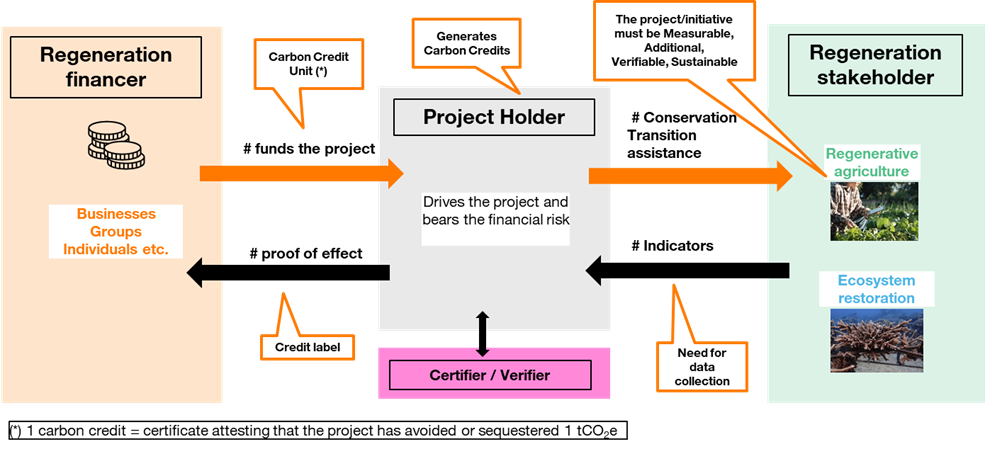

The ecosystem of players for voluntary carbon offsetting can be relatively complex[7]. However, the following key roles can be identified:

- The end customer (regeneration funder) who buys carbon credits to offset their emissions,

- The project holder who addresses a community of stakeholders whose activities promote carbon sequestration and regeneration.

Key roles of the carbon offsetting process

In order for this trading market to be reliable and credible, it is important to rely on a certification system to verify the compliance of carbon offsetting projects. This is what is called a carbon standard. The two main standards used in the voluntary carbon market are the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS)[8], developed by Verra, and the Gold Standard[9].

What barriers need to be removed to set up an African carbon farming ecosystem?

Implementing carbon farming comes with some challenges, such as the complexity of the processes and the lack of appropriate local regulations[10]..

In addition, there are still several difficulties related to getting African producers involved:

- They must quickly see the benefits of these new practices in their production, especially on yield.

- They must be trained in conservation farming techniques related to their agricultural activity and this requires setting up a network of agricultural advisors whom they trust.

- It is also necessary to implement a system that allows them to receive early compensation to help encourage them to switch over.

But one of the main obstacles is creating a reliable link between regeneration players and funders through the voluntary carbon credit market. This involves risks for companies looking to offset their emissions. To prevent large-scale fraud, intermediaries and project backers must all be trustworthy. The main difficulty is guaranteeing the integrity and authenticity of carbon credits issued. To do this, an MRV (measurement, reporting, verification) system is required to monitor the environmental impact. However, there is not yet a unified international methodological framework. The ORCaSa project has identified different guides and calculation methods, with the aim of unifying MRV systems while adapting them to specific local needs. This work is continued in an international framework within the Soil Carbon International Research Consortium, whose ambitions include proposing a harmonised MRV framework[11].

The first barrier is therefore technological and consists of being able to quantify the carbon in the soil. Measuring this is one of the keys to the offsetting system. To do this, we must be able to implement low-cost reliable solutions.

Regarding the Measurement part, a recent study compared several methods for assessing soil organic carbon in small farms in Kenya. These methods include laboratory-analysed samples, sensor-collected data, satellite imagery and modelling. The main criteria are the benefits for producers, the cost, the measurement quality and their adoption as a standard.

Although satellite technologies currently appear as less precise solutions, they are beginning to be considered in the standards. Let’s take the example of Boomitra[12], which received a Verra certification in 2025 with its MRV system powered by AI and satellite images. Today, this shows a potential that is important to explore.

The main goal of Orange Innovation’s research project “From Space to Field” is to investigate the use of satellite images analysed with artificial intelligence to detect early anomalies (such as diseases and deficiencies) and support small producers by offering them advice on more sustainable agricultural practices. ZitApp[13], an app developed for Tunisia’s olive industry, makes it easy to achieve these goals with just a few clicks. It was designed through regular interactions with potential users and players in the Tunisian olive ecosystem. Tests demonstrated user interest, allowed us to refine the solution and identify potential developments, such as introducing a chatbot to further simplify its use.

The same technical basis (AI analysis of satellite images) could be used to detect carbon sequestration potential in agricultural plots.

An opportunity for Orange

In line with Orange’s purpose of being “a trusted player that paves the way to a responsible digital world welcoming each and every person”, its research teams are exploring the potential of remote sensing and AI to effectively measure carbon sequestration in soils. The work, carried out in partnership with CRNS (Centre de Recherche en Numérique de Sfax — the Digital Research Center of Sfax), aims to develop tools capable of estimating aerial and underground biomass—key indicators of carbon capture—through the analysis of satellite images and the leaf area index. The models developed will be corroborated by the field observations of expert agronomists from the Institut de l’Olivier (Olive institute).

The objective going into 2026 is clear: to provide African producers with a simple, accessible and reliable service to evaluate the carbon sequestration potential of their land, and thus support them in the transition to sustainable and remunerative agriculture.

In conclusion, carbon farming is not only a response to climate and agricultural issues, but also a great development opportunity for Africa. By combining digital innovation, supporting producers and promoting environmental services, Orange is aiming to help cultivate more resilient, equitable and sustainable agriculture.

[1] https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/unearthing-soils-carbon-removal-potential-in-agriculture

[2] United Nations Climate Change Conference | United Nations

[3] https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

[4] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/bodies/constituted-bodies/article-64-supervisory-body

[5]https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/A6.4-SBM014-A06.pdf https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/A6.4-SBM014-A05.pdfhttps://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/A6.4-SBM014-A05.pdf

[6] https://www.actu-environnement.com/blogs/boris-martor/455/aval-cop-29-une-relance-marche-carbone-volontaire-718.html#_ftn1

[7] https://librairie.ademe.fr/changement-climatique/5708-la-compensation-volontaire.html

[8] Verified Carbon Standard – Verra

[10] See Africa Carbon Markets: Status and Outlook Report 2024-25, pp. 32–35

[11] https://soilcarbonfutures.earth/about/

[12] https://africanfarming.net/magazines/af_2025_05_26/spread/?page=16

[13] Prototype integrating CRNS algorithms

Sources :

- “Carbon farming in Africa: Opportunities and challenges for engaging smallholder farmers”[1] March 2023.

- The works of Abdelaziz Kallel, Researcher at CRNS, Digital Research Center in Sfax

Read more :

Carbon sequestration: An essential tool against climate change

Despite the proliferation of initiatives to reduce emissions, the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere is continuing to rise, accelerating global warming. “According to Copernicus’ observations, 2025 is on course to be one of the warmest three years ever recorded.” – Copernicus: 2025 on course to be joint-second warmest year, with November third-warmest on record | Copernicus

In the face of this emergency, carbon sequestration—this “trapping” of CO₂ by oceans and lands—is a necessity now more than ever. Yet the delicate balance between emissions and natural absorption has been disrupted: Current carbon sinks are no longer able to offset the surge in emissions.