In order to succeed, students need to help each other, therefore talk with other students

Summary

Professional training is trending towards digitalization. Companies turn to it to reduce their budget and to accelerate acquisition of knowledge by their employees. But how is it for the “learners”? Orange has studied attendance at online courses by employees, their motivations, and their reasons for succeeding or for giving up on the way.

The study examined a group of 20 learners following a course that was mainly aimed at the training community within Orange. Their motivations were very varied: to update their knowledge, to learn a concept, the desire for professional development, etc. Only 10% of learners went as far as the final certification. This low “success” rate should be kept in perspective. Some did not need the final certificate, but just wanted to complete their subject knowledge or master the vocabulary. Others still, cited the time spent on the lessons, which was longer than expected, or a busy diary.

The study made several observations. Firstly, stopping does not mean giving up! Then, that digital does not replace face-to-face contact. In order to succeed, the learners need to help each other, therefore to exchange with other learners. Finally, the online learning facility must include technological, educational, and organisational dimensions.

Full Article

How using digital technologies for continuing learning in enterprise?

In recent times, efforts to digitalize continuing education have been stepped up with the twin aims of keeping training budgets under control and accelerating innovation by enabling employees to acquire skills more quickly… but, from the perspective of the employees who enrol as learners, what does taking an online course really mean?

Based on a qualitative survey of 20 learners at various stages of completion of the COOC (Corporate Open Online Courses) «Digital Learning», this article aims to shed light on the significance of learners’ abandonment or successful completion of this course in a range of contexts. The COOC, which was held over a six-week period in the second half of 2015, was designed primarily for Orange training personnel, but also attracted a number of learners from other parts of the company (communications, business line coordinators, etc.).

A long history of digital technology in training

From self-training, to e-learning, to digital campuses and digital workspaces, most of experiments have been marked by high dropout rates. A number of studies have been conducted to investigate learners’ failure to complete such courses. Some of these focus on the role of teachers, tutors or guides. Others [1] stress the role of collectives of various kinds in maintaining a dynamic of sharing and exchange that is conducive to learning. One of the reasons why social bonds are important in learning is that they promote learner engagement [2]. In a similar vein, other studies [3] underline not only the importance of factors relating to the individual (motivation, initial confidence level) and those connected to the training system (learning process, support from teachers), but also the role of peers in providing social and emotional support.

The “enabling environment” approach applied to vocational training [4][5] shows the extent to which the technological, educational and organizational dimensions are interlinked, for learners, trainers and educational engineers (course designers) alike. It shows how the success of a course depends on the way in which educational use of digital technologies is envisaged as part of the wider organization of work.

The importance of individual, collective and organizational contexts in distance learning

The COOC we looked at was targeted at Orange training personnel (trainers, educational engineers, etc.) and aimed to boost their knowledge of digital usage practices within the context of their work. It made use of a number of digital resources, including online content, links to reference texts, videos, quizzes, and social forums. To obtain a certification badge at the end of the COOC, learners had to successfully complete the first six weeks, testing their knowledge through quizzes, then, in the seventh week, write a dissertation. Less than 10% of learners who enrolled obtained the badge.

Motivations for taking the COOC

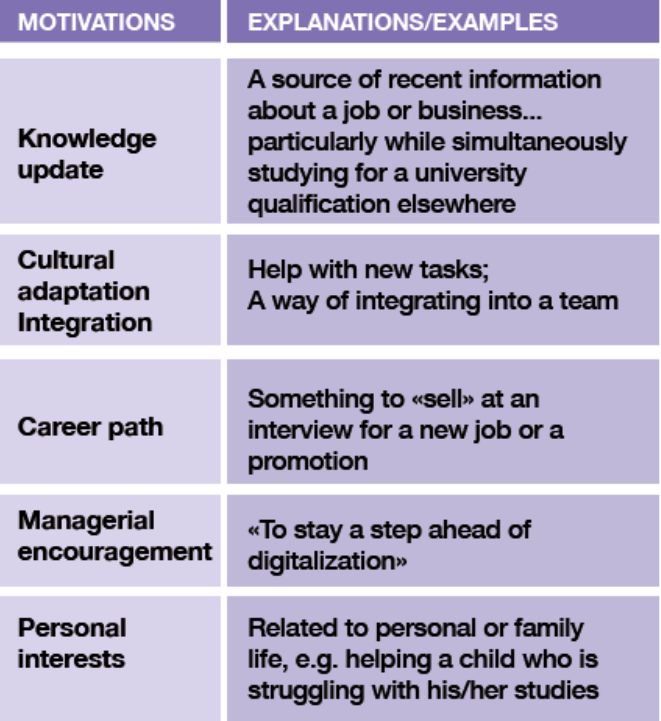

We have divided these motivations into five categories, as summarized in the table below.

Fig. 1 Motivations for taking the COOC

Some of the learners interviewed signed up for the course primarily to update their knowledge of how digital technology can be used in their business or for their job. This was especially true for trainers and educational engineers, who wanted to get an idea of which new tools they could use in their field.

Other learners decided to take the course to gather additional information on specific points relating to the use of digital technology for educational purposes. They saw the time spent on the course as comparable to «time spent in a library». For these two categories of learners, then, not validating the seven modules does not constitute dropping out or abandoning the course: on the contrary, they are showing their desire to be active players in their own training and learning, which is perfectly in keeping with the spirit of MOOCs and COOCs.

For another fraction of the learners, taking this course reflected a desire to acquire new skills so as to be able to take on new tasks, be it as a trainer or as a communications manager.

Some employees, particularly young apprentices, saw taking the course as a way of integrating into a working group, by learning the essential vocabulary and the concepts.

Others decided to take the course precisely because it led to certification and they thought that they would be able to «sell» this certification later at an interview for a new job or a promotion. These people are young apprentices or interns who want to take advantage of the opportunities the company gives them to acquire advanced skills. Their attitude stands in stark contrast to that of more experienced employees, who are much less convinced of the value of this certification for their career.

Irrespective of any certification- or career-related considerations, the possibility of taking the entire course remotely and asynchronously is seen as an opportunity to bypass face-to-face classes for those who travel a lot for work and indeed for those who have found their duties as a facilitator taking up more and more of their time. For them, taking this COOC outside of work time is the only way to keep up to date with the latest developments in the digitalization of coordination and training.

Finally, some learners enrolled in the course for non-work reasons. This was the case for some employees whose children are having difficulties at school, who saw the COOC as a way of accessing new information to help their children overcome their problems.

Organizing time for taking the COOC

The time necessary to complete the various tasks required to validate each module also provides an explanation for dropout rates. The individuals interviewed said they had spent more time on the COOC (4 hours on average) than the time initially anticipated by the designers (2 hours). Learners’ ability to make progress with the COOC also depends on the amount of leeway they have to organize their time. Several learners reserved time slots in their diary, but more often than not had to move them, or even give up on them entirely. Some sacrificed some of their free time, while others gradually fell so far behind that they had to give up.

Some communications operatives, network coordinators and other professionals far removed from training, found that the time they spent on this course was sometimes seen by their peers as «leisure time». «Peer review» can therefore be an obstacle to following a.

The variety in learners’ backgrounds, experiences, jobs and organizational settings leads to considerable variation in the time allotted for following or validating the various modules. Work activities also impinge on the private sphere differently, and we have seen differing abilities to keep up with the pace of the COOC.

However, some employees managed to overcome their time constraints and to validate the sixth and even the seventh week. We believe this can be explained by the fact that these individuals were able to seek assistance from at least one other learner. Another major factor is the possibility of engaging in face-to-face exchanges with co-learners,, the crucial point being that the learners should have met before the COOC begins.

In other cases, the feeling of having dropped out comes from a perception that the COOC will be of little benefit for the learner’s work or career path. This could be due to a lack of recognition of the certification offered at the end of the course or an absence of links with cross-cutting business line coordination networks that would allow a more operational implementation of the knowledge imparted.

© Andrey Popov / Shutterstock

Face-to-face interaction: an antidote to abandonment?

First of all, we can assert that some of those who stopped mid-course did not give up, but were, from the outset, simply looking for additional information, not certification. Whether or not they obtained knowledge from the course, their aim was never to finish it.

Furthermore, those who obtained their certification, either had all previously worked (albeit remotely in some cases), with at least one of the other learners, or first met just before embarking on the COOC and exchanged then with their peer (by telephone or face to face) to provide mutual support. As several interviewees pointed out to us, the possibility of receiving support from a peer depends largely on how much trust you place in them. They say, asking for support means showing that you haven’t understood, exposing yourself to judgement, taking the risk of admitting that there are gaps in your knowledge, which, in a climate of competition between individuals, has consequences.

Conversely, some of the learners who gave up did so because they did not know any colleagues who they could trust enough to ask for help.

© Rawpixel / Shutterstock

Using the digital tools provided could not compensate for the initial lack of face-to-face contact (for those who did not know each other and did not take part in the launch seminar).

Conclusion

These results remind us of the extent to which technological elements, educational dimensions (balances between presence and distance), and organizational aspects (recognition of the usefulness of the COOC, support from managers by allocating the necessary time for the course and allowing learners to put the knowledge imparted by the COOC into practice, etc.), are interconnected. The much vaunted 100% distance learning runs up against the organizational constraints, and particularly time constraints, of employees’ working lives. The fact that learners do not always make it to the end of the COOC is one symptom of the disconnect between the desire to make training faster and more efficient and reallife organizational considerations.

An in-depth study of course abandonment, or, to be more accurate, apparent course abandonment, also highlights the variety of attitudes employees take to the opportunities COOCs offer. For some, the modular structure, asynchronous pace and digital content constitute opportunities to access information that they consider to be useful for their work or their future career prospects.

The reach of the results of this study is broad. It concerns all the digital systems for vocational training: when designing this type of system, the key is to consider carefully how these technological, educational and organizational aspects can be reconciled.

More info

MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) : online course aimed at unlimited participation with open access via the web

COOC (Corporate Online Open Course) : online courses organized by companies to their employees

SPOC (Small Private Online Course) : online tailor-made courses, aimed to a small group of people

[1] Metzger J.-L., « De L’importance des collectifs dans la formation en ligne », Formation emploi, n° 90, 2005.

[2] Molinari G., Poellhuber B., Heutte J., Lavoué E., Sutter Widmer D., Caron P.-A., « L’engagement et la persistance dans les dispositifs de formation en ligne : regards croisés », Distance et Médiation des Savoirs, n°13, 2016.

[3] Dussarps C., « L’abandon en formation à distance – Analyse socioaffective et motivationnelle », Distance et Médiation des Savoirs n°10, 2015.

[4] Boboc A., Metzger J.-L., « La formation professionnelle à distance à la lumière des organisations capacitantes », Distance et Médiation des Savoirs, n°14, 2016.

[5] Boboc A., « Un environnement capacitant pour accompagner la transformation numérique de la formation professionnelle », Interview pour le blog de la plateforme Solerni, juin 2016.

partie 1

partie 2