This ergonomic research examines these questions using the results of collaborative research conducted in partnership with museums (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, Louvre Lens, Musée d’Orsay).

To lead this investigation, there is an important distinction between the visitor’s emotional relationship with the exhibits and his/her analytical relationship with them. The emotional relationship involves the visitor allowing his/her impressions and sensations to rise to the surface upon viewing the work, and further exploring the work by use of his/her imagination. The analytical relationship, meanwhile, allows the visitor to keep the work at a distance, to look at it objectively and distinguish its different parts. Though the distinction between these two relationships is useful for the analysis, the two may occur exclusively, sequentially or concomitantly [1].

Individual use of augmented reality at the musée des beaux-arts de rennes

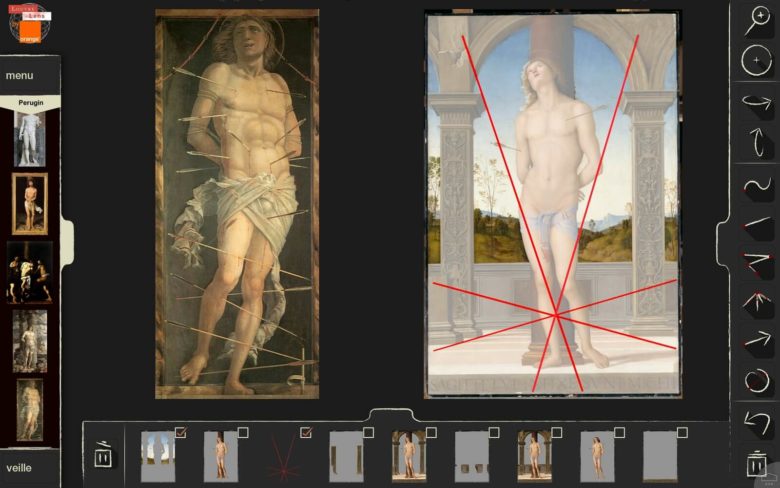

In this experiment, visitors spent around 45 minutes exploring the museum alone, equipped with an audio headset and a tablet containing an AR guide. To understand how the augmented guide transformed visitor activity, it was necessary to identify the usage frameworks (different ways to use) associated with it [1] [2]. The main findings are concerning the approaches implemented by 16 visitors wandering around the museum on their own. To access the Augmented Reality features, the visitors had to position themselves in front of the right work of art and frame it with a tablet that was filming the real environment. When the visitor points the tablet at a relevant work, digital content is displayed on the screen, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A visitor using the AR guide at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes

Three approaches to using the augmented guide have been identified:

The video approach: This is when a visitor constantly looks through the guide as they move around the museum. Consequently, visual exploration with the naked eye is diminished, with visitors suffering from significant tunnel vision and, ultimately, giving primacy to the technology over the art. This was the predominant approach of 5 visitors.

The quickfire photos approach: This is when a visitor first looks at the works with the naked eye so as to locate them in the space, then frames and photographs them with the augmented guide. Their gaze is sanctioned and fragmented by the device, as one visitor explains: “When I’m looking for the red spot, I have thought about things backwards: I am wondering which painting I’m going to be led to. I didn’t think about which one I would go towards, but which one they would try and direct me to. I try several paintings”. This was the approach used by 7 visitors.

The moderate photo approach: This is when the visitor looks at the works with the naked eye (considerable visual exploration) and takes only a few photographs with the augmented guide. The device provides clues that guide visitors’ exploration of their environment. Even if a person is capable of discovering the relevant details, the device enriches and guides their visual exploration of the exhibits. This approach was the main strategy used by 4 visitors.

Visitors’ approaches may leave them closer to or farther away from the reality of the work. Given the pedagogical aims of such establishments, the moderate photo approach is the best suited and prevents users from becoming too detached from the reality of the works. With this in mind, Augmented Reality should not aim to provide exhaustive information, but rather to provide clues that invite the visitor to identify, with the naked eye, the relevant element initially highlighted by the system.

However, some features of the augmented guide seem to give priority to the visitor’s emotional relationship with the work. One-third of visitors stressed the importance of audio accompaniment in boosting their emotional relationship with the work: “It creates a sonic landscape. I feel really immersed ”/ “The roar of the tiger brings the painting to life”. Sound and music could therefore be more widely used by Augmented Reality to help visitors immerse themselves in the here and now of the art and deepen their relationship with the works through their imagination.

Group use of augmented reality at the louvre lens

A few years later, as part of an Orange partnership, it was an opportunity to carry out experiments to study and compare how users got to grips with two digital systems in a real-life group mediation situation. In the first session, visitors were equipped with tablets connected to a “master” tablet controlled by the mediator. In the second, they were equipped with smart glasses connected to a “master” tablet controlled by the mediator.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the interface available on the mediator’s tablet

Functions enabling the user to zoom in on, point at and trace the works of art could be activated by the mediator in real time (see Figure 2). For visitors wearing glasses, explanations could be superimposed on the works themselves. For tablet users, such explanations were simply displayed on-screen. The smart glasses were therefore akin to an AR system, whereas the tablets (without AR) provided us with a point of reference with which to compare.

Each session of thematic tours in which the mediator accompanied small groups of around ten people to help them enjoy a more in-depth exploration of the work of Saint Sébastien du Pérugin lasted approximately 20 minutes. These observation sessions deliberately involved a varied audience (children, young adults and adults). At the end of the observations, interviews with the mediators and visitors confronted to the videos were necessary in order to enrich and fine-tune the analysis.

To this end, the number of times the mediator pointed to or moved towards the work were counted, to check that the work remained central and that the AR did not hinder the visitor’s emotional relationship with the work. The number of times the mediators asked the visitors questions were also counted, and the number of times the visitors took part in group discussions, so as to measure the impact of each device on visitor-mediator interaction.

- Impact of smart glasses on interaction

When the visitors were equipped with smart glasses, the mediator rarely pointed to or moved towards the paintings (15 times, as opposed to 57 when the visitors had tablets). The visitors with glasses concentrated on the voice of the mediator, meaning the works of art were therefore mostly perceived through the glasses and the content displayed. In this configuration, the mediators expressed unease and a feeling of being out of sync with the visitors: “I had trouble knowing what they thought of the painting. I didn’t get any feedback from them.”

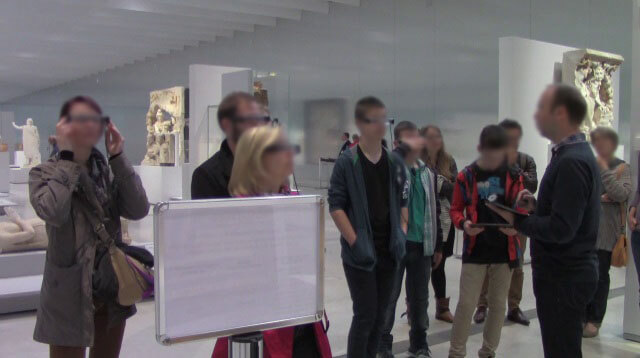

The visitors, meanwhile, highlighted the isolation the glasses produced: “We are isolated from the mediator and from the others” / “It creates distance” / “You can’t get at the work directly”. As the photos show (Figures 3, 4, 5), the mediator and the visitors were stuck in the same position throughout the mediation session.

Although the augmented glasses helped keep visitors’ analytical concentration levels high, they hindered and diminished their emotional relationship with the works. “You are very focused on what the mediator is saying; it’s not the same relationship, you cannot move easily around the work; I can’t imagine anything if I am too focused on analysis”. The visitors’ comments suggested an analytical focus that prevented the kind of mobility and free movement that might be conducive to a more emotional relationship with the works and to imaginative thinking.

Despite these obstacles, visitors played with the content displayed on their glasses, demonstrating two kinds of strategies:

- Some projected the screen of their glasses onto a fixed plane, then kept switching back and forth between that plane and other locations;

- Others tried to superimpose the information displayed in their glasses on the real works by moving their head (“It’s like a piece of tracing paper”).

The latter are in the minority, however, with most visitors seeking to keep the information projected on the screen of their glasses still in order to avoid feeling dizzy, consistently looking at the floor, the mediator’s sweater, their own hand, or the picture rail next to the work.

Figure 3: Visitors wearing smart glasses

- Impact of tablets on interaction

In contrast to smart glasses, the tablets encouraged private conversations as well as group discussions. The work remained the primary focus, and was given pride of place by the mediator, who constantly moved between the art and the visitors.

Figure 4: The mediation session with tablets enabled private conversations to take place (mother and child in the bottom left, couple on the right), but also allowed visitors to join the group during the session (man in red sweater).

Micro-exchanges took place between parents and children. This was an aspect mentioned both by the mediator (“I felt that they were free, and not at all glued to the tablet”) and by visitors (“in terms of showing things to children, the tablet allows them to touch and point to things, which you can’t usually do on the painting itself”).

This system was popular with visitors, as it left room for them to explore the work and allowed each individual to plot his or her own path towards the work, supporting both the analytical and the emotional relationship. Visitors explained that this form of mediation left room for the emergence of a unique, personal perception: “I think this kind of mediation makes it possible for us to focus on what we are feeling, whereas when you are alone in front of a painting, you don’t always ask yourself those questions. Here, you’ve got the explanation, the symbol and the context. Those things allow you to listen to your emotions, which you might neglect if you were alone”. As Figure 5 shows, the mediation space is once again occupied by the body of the mediator, who moves around in the space, creating fluid movement between the visitors, the mediator and the works. Visitors are more animated, speak and can develop an emotional relationship with the works before their eyes.

These two studies reveal the need for the visitor to alternate between augmented and naked-eye exploration. In this context, Augmented Reality seems more relevant when it reduces the complexity of reality to direct the visitor towards further exploration of their environment. This prompts a crucial question: how can Augmented Reality enable the user to engage in both an analytical and an emotional response? How can Augmented Reality be designed to immerse the subject in their environment?

At the musée d’orsay: a potential tool for immersion?

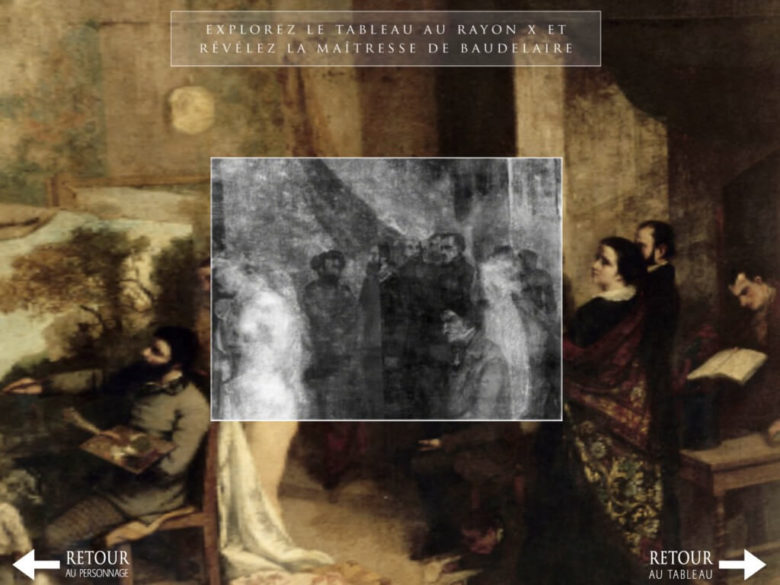

This is what a third collaborative research project with the Musée d’Orsay achieved on the application “Entrez dans l’atelier du peintre” [“Step into the artist’s studio”] based on the Courbet painting, “The Artist’s Studio”. It was a good opportunity to apply the lessons learned from past research, opting for open narration (the narration is done through monologues that the visitor can trigger whenever they like, in whatever order they want) to help stimulate visitors’ imagination, as well as combining interactive modules with audio modules.

The experiments (augmented exploration of works on a tablet), carried out with around thirty visitors, revealed that visitors alternated between an emotional relationship with the artwork (with the focus on direct exploration of the work, while listening to the monologues of the characters in the painting), and an analytical relationship when they used the infrared ray modules (See Figure 6). This alternation creates a fictional space that is explored with curiosity by two-thirds of participants and deemed too disruptive and different from usual (i.e. lecture-style) visiting formats by the remaining third.

Figure 5: Illustration of the interface enabling infrared photographs to be superimposed on the real painting.

The combination of visual and audio resources (Figure 6) bothers a third of visitors, however. Visitors are sometimes also disoriented by the choice of non-linear narration, as the monologue of each character is triggered when the visitor aims at a character with their tablet. In contrast, two-thirds of visitors appreciate this non-linear narration, which allows visitors to play, move around within the work and allow their imagination to run away with them.

These three fields of research in a museum context stress the importance of leaving users spaces that contain no Augmented Reality information so that they can wander around and get lost, and of opting for systems that encourage easy alternation between direct access to the work and access via an AR device. This need for alternation between superimposed virtual elements and the unmediated real world is at the heart of our digital activity; giving users spaces of freedom so as to promote productive alternation between providing knowledge and stimulating their unique personal perception of a work of art.