• The definitions and classifications of these risks set out by government institutions or companies do not always match up with how individuals perceive them.

• To craft tailored protective solutions, it is necessary to understand how Internet users perceive risks. The risks inflicting real or perceived harm on Internet users are at the heart of this research.

What do you think of when you hear the term “digital risk”? Some people will answer “cyberbullying”, while others cite “phishing”, “cryptocurrency” or “identity-related crimes”. A few won’t have an answer, but most will mention “hacking”. These answers are translations from real transcripts obtained during a survey of 2000 people in France in January 2024 [1].

Using digital technology comes with many risks. Risks related to cybersecurity are receiving more and more media coverage — and yet, just like with cyberbullying, the definition of digital risk remains unclear for many.

This article explores the different ways to define digital risk and proposes a new theoretical framework. It is part of a doctoral thesis in sociology [2] and research aimed at understanding how risks related to cybercrime are perceived by Internet users on an individual level in order to create preventive and protective systems. Institutional definitions will be presented, and the specific case of bank fraud will be explored further. An analytical framework for online risks will then be proposed.

The boundaries of cybersecurity are blurry

“Online risks” have become a major area of concern in recent years, catching the attention of governments, businesses and researchers alike. The challenge of conceptualising “online risk” is key in Orange’s research and efforts to bring online security to the general public.

Online risks are often seen as synonymous with potential security issues, meaning they are addressed in conjunction with the concept of cybersecurity. However, as a 2019 informational report from the French National Assembly highlighted, the concept of cybersecurity is not well defined. It states that “whether the focus is on the means of achieving it or its intended purpose, cybersecurity would therefore be a state of minimum vulnerability and stability against potential threats that may prevent information systems from operating correctly”. Cybersecurity and the risks it seeks to prevent encompass many situations.

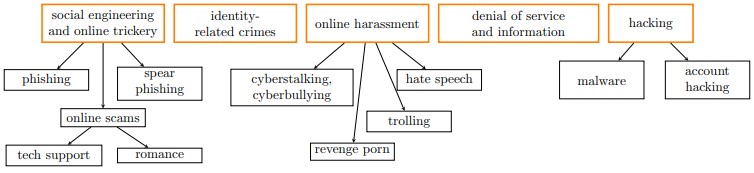

Figure 1. Taxonomy of cybercrimes against individuals. Source: J. R. Nurse (2018). Cybercrime and You: How Criminals Attack and the Human Factors That They Seek to Exploit. arXiv, abs/1811.06624.

On 21 May 2024, a law aimed at securing and regulating the digital space (the SREN law) was enacted [4]. With the stated aim of “restoring the trust necessary for the digital transition to succeed”, it puts forwards a number of cybersecurity measures to combat online scams and harassment, and to strengthen sanctions for these violations. In addition, this initiative aims to protect children from online pornography, while also regulating cloud companies, monitoring tourist rentals and managing online gambling. Cybersecurity therefore encompasses a wide array of risks. This law is in addition to several government initiatives aimed at regulating the Internet.

In the business world, ANSSI (Agence Nationale de la Sécurité des Systèmes d’Information — the French Cybersecurity Agency) is responsible for ensuring online security for businesses and government agencies. Risks and security are considered across a business and include cyber defence measures. Cybersecurity, a term often associated with risks to businesses, is being increasingly used for individuals too.

Cybermalveillance.gouv.fr is a national scheme that supports victims of malicious activity online. It monitors and prevents digital threats, and also plays a role in prevention and raising public awareness of cyber risks. It uses the terms “cyber scams” and “cyber crime” to categorise security issues on the Internet. It defines cyber crime as “any offence committed digitally”.

The CNIL (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés — French National Data Protection Commission), states that it is “dedicated to cybersecurity”. In addition to supporting professionals, it also raises awareness among the general public about what it calls “cyber risks”. These risks are numerous and include security issues related to personal data. Unlike Cybermalveillance.gouv.fr, these security incidents may or may not be malicious, and may or may not be intentional.

These organisations’ approaches complement each other and provide an institutional framework for different risks. Alongside this there is the specific risk of payment fraud.

Digital payment fraud mainly affects individuals

Internet users are targeted by increasingly sophisticated online attacks that aim to lose them money. In many cases, this means bank fraud. The OSMP (Observatoire de la Sécurité des Moyens de Paiement — French Observatory for the Security of Payment Means) defines bank fraud as “the illegitimate use of a means of payment or the data associated with it, as well as any actions that contribute to planning or carrying out such use”. In 2022, 8% of French people were affected by payment fraud [3]. That figure stands at 13% for 2024 [4]. Yet while these numbers may seem high, they fall far short of including every case of Internet users being affected by malicious activities or having lost money as a result of a scam. In fact, some types of scam or fraud are not included in this definition — such as when an Internet user makes a payment to a malicious character themself, or when the objective is not to withdraw money directly, but instead to obtain an individual’s bank details to later carry out a more elaborate fraud. Similarly, Internet users may consider commercial scams—such as products that do not match their description—to be risks, while some institutions such as banks do not. Beyond fraud, it is therefore necessary to focus on all the digital security issues experienced or perceived by users and the risks associated with them.

Towards a sociological understanding of online risks

In taking a sociological approach, the goal is to move beyond institutional definitions and explore online risks through individuals’ experiences and perceptions. This approach is part of a perspective that looks at risks not as objective entities, but rather as social constructs shaped by cultural, economic and contextual factors [5]. Although the scientific literature on this subject is not particularly extensive, there are several studies that have explored it — but in rather disparate ways.

David Bounie and Marc Bourreau [6] demonstrated that the risk of online banking data theft has an effect on the consumption of some Internet users, while Camille Capelle and Vincent Liquète [7] studied how the way in which digital risks are perceived impacts teaching methods. According to Capelle and Liquète, “digital risks can be thought of as threats that may arise during or as a result of a digital activity, some more dangerous in nature than others, and that are likely to impact the user or have harmful consequences for others”. Jean-François Céci [8] demonstrates that some digital risks impact health (exposure to waves, screen addiction, hyperconnectivity, attention disorders), while others have socio-political implications (energy overconsumption, electronic waste, widening accessibility issues, uberisation, facilitation of terrorism, Taylorisation of jobs to the extreme, hacking, misinformation etc.). Sonia Livingstone takes a comparative approach to examine the risks European children face based on their level of Internet use [9].

These studies struggle to account for the diversity in how Internet users perceive risks. A new methodology is proposed to enhance these approaches. It involves first understanding what constitutes a risk for Internet users, then how they adapt to it, and finally developing appropriate preventive and protective measures. This approach expands on existing ideas by focusing on the user perspective. These perspectives are analysed through semi-structured interviews and quantitative surveys. These demonstrate that users’ perception of risk and the practices they use to avoid it differ depending on their personal profile, their digital experience and the people around them. The next step is to understand how these risks are interpreted and managed as part of their daily digital practices.

Different categories of Internet users perceive risk in different ways.

French people’s relationships with the risks they encounter online have been examined through a number of research projects. First and foremost, the term itself does not make sense to many. Furthermore, when asked what constitutes a digital risk for them, the majority associated it with hacking above all else. For them, the meaning of hacking is not confined to its definition: “Gaining unauthorised access to an asset such as a computer, server, network, online service or mobile phone.” Interviews [10] have shown that there is a lack of clarity among Internet users about the risks they face online. They associate hacking with other types of attacks that worry them more, such as online scams or bank fraud. Similarly, issues related to privacy are melded with those related to hacking. Scams are confused with unfair trading practices, drop shipping with fraudulent websites and so on. Although people may feel victimised, these are not types of fraud or scams. The reasons for this lack of clarity are undoubtedly rooted in the plethora of terms related to cybersecurity, an overload of disparate advice [11] and even contradictory instructions [12].

Perceptions also differ based on personal profiles, experiences and life stages. Some of those surveyed thought it risky to buy from a certain website, while others considered it highly convenient and frequently made purchases there. Some saved their payment information on their phone (with Google Pay, Apple Pay etc.) after seeing their friends do so, whereas one removed her details following a warning from a friend. Finally, people accepted or rejected cookies depending on perceived risks, advice and Internet users’ view of their usefulness.

To be able to raise awareness and develop protective solutions, it is necessary to redefine risks based on how they are perceived by users.

The proposed approach to researching risks is giving individuals a voice in order to understand their subjective experiences [13].

Studying risks involves looking at threats that may arise during or as a result of a digital activity and are likely to affect the user or have harmful consequences for others. These consequences may be real or perceived. This includes viruses, hacks, scams and other online situations where individuals have lost money and felt victimised. It involves considering risks in their social and cultural context, and exploring factors that influence individuals’ perceptions of these risks. This approach paves the way for a nuanced and contextualised understanding of online risks, with an emphasis on the rationale behind actions and the strategies individuals use to adapt. This will help to develop appropriate preventive and protective systems.

Taking a user-centric approach to cybersecurity is part of the drive to create a trusted digital environment that facilitates inclusion.

While digital risks have been studied for a long time [14], recent developments have raised new questions. Alongside efforts made to democratise digital access and promote digital inclusion, notably including those by governments and Orange, it is necessary to consider the challenges that this inclusion will bring. Today, individuals who are not very active online, particularly in terms of financial transactions, are targeted less than regular users with similar profiles [1]. With support for digitalisation and the growing push for more online transactions, there is a danger of a surge in people falling victim to attacks. Awareness of digital risks must accompany the digital inclusion process. Initiatives such as the Orange Cybersecure offering are steps in this direction. The research presented above contributes to the development of preventive strategies based on the concrete experiences of users. It is part of Orange’s strategy to build a secure digital society, aligned with its purpose: to be “a trusted partner, giving everyone the keys to a responsible digital world.”

Glossary :

Social engineering

The use of psychological manipulation for fraudulent purposes.

Phishing

Fraudulent messages using social engineering techniques that aim to steal users’ login credentials, passwords or bank card details.

Spear phishing

A type of phishing where the recipient is targeted, as opposed to phishing attacks which are more large-scale and generic.

Sources :

[1] OpinionWay study for Orange, « Les Français face aux risques numériques », 2024.

[2] Coly, A. (2022-2025). Usage de l’argent en ligne des jeunes adultes et risques associés, [Cifre doctoral thesis ongoing]. Université Gustave Eiffel, Orange Innovation.

[3] OpinionWay study for Orange, « Les Français et la fraude bancaire », 2022.

[4] OpinionWay study for Orange, « Les Français face aux risques numériques », 2024. The question asked was: “On one or more occasions in your personal life, have you yourself been the victim of BANK FRAUD?” This was preceded by a definition of fraud: “Here, the term ‘bank fraud’ is used to mean any fraudulent use or trickery, a scam, or the theft of one of your payment methods, your chequebook, your bank card (CB, Visa, Premium, Mastercard, Infinite etc.) or your bank account number, to make a payment, a transfer or a debit without your consent or against your wishes. For the purpose of this study, we are not interested in unfair commercial practices (e.g. purchases where goods were not received, not compliant or past their expiry date).”

[5] Granjon, Fabien (2012). Reconnaissance et usages d’Internet: Une sociologie critique des pratiques de l’informatique connectée. Presses des Mines. isbn: 978-2-35671-092-5. doi: 10.4000/books.pressesmines.252.

[6] Bounie, David and Marc Bourreau (2004). “Sécurité des paiements et développement du commerce électronique”. In: Revue économique 55.4, p. 689. issn: 0035-2764, 1950-6694. doi: 10.3917/ reco.554.0689.

[7] Capelle, Camille and Vincent Liquète (2022). Perceptions et analyses des risques numériques. Vol. 1. Londres: Iste. isbn: 978-1-78405-866-1.

[8] Céci, Jean-François (2019). “Vers Une École Du Risque Numérique ?” In: Annales des Mines – Enjeux Numériques. Répondre à La Menace Cyber N◦8.

[9] Livingstone, Sonia and Ellen Helsper (Aug. 2007). “Gradations in Digital Inclusion: Children, Young People and the Digital Divide”. In: New Media & Society 9.4, pp. 671–696. issn: 1461-4448, 1461-7315. doi: 10.1177/1461444807080335.

[10] Semi-structured interviews conducted with young adults (aged 18 to 29) between January and February 2024.

[11] Reeder, Robert W., Iulia Ion, and Sunny Consolvo (2017). “152 Simple Steps to Stay Safe Online: Security Advice for Non-Tech-Savvy Users”. In: IEEE Security Privacy 15.5, pp. 55–64. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2017.3681050.

[12] For example, in a radio show in June, the Director of Cybersecurity Expertise for cybermalveillance.gouv.fr said that regularly changing your password is not necessary, despite this being a widely recommended practice. (Radio France. (2024, juin 5). Arnaques en ligne : les nouveaux cambrioleurs. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/entendez-vous-l-eco/arnaques-en-ligne-les-nouveaux-cambrioleurs-3463631)

[13] Pasquier, Dominique (2018). L’internet des familles modestes: enquête dans la France rurale. Sciences sociales. Paris: Mines ParisTech-PSL. isbn: 978-2-35671-522-7.

[14] Gire, Fabielle, et al. (2006). Représentation des risques et pratiques de sécurisation des internautes en France, Issy-les-Moulineaux, rapport FTR&D.