The qualitative survey we conducted among 55 users of four sites (BlaBlaCar, Drivy, Videdressing and Co-Recyclage) aimed to document this reality.

Making transactions “nice”, together

We were struck by the importance of considerations regarding what should be done, or what should be avoided, to ensure that collaborative transactions go smoothly and to make them “nice”. This joint development of good practices is facilitated by the fact that consumers have more empathy with other consumers than they do with professionals. 33-year-old sound technician Aurélie, for example, does not argue with the meeting points suggested by drivers on BlaBlaCar: “I don’t want to put the driver out“. Another factor that makes them even more willing to put themselves in the provider’s place is the fact that they themselves often play both roles – the same person may use BlaBlaCar as both a driver and a passenger, or be a provider on one platform (selling possessions on Le Bon Coin, for instance) and a recipient on another (e.g. renting cars on Drivy).

The joint tasks that providers and recipients set for themselves and each other are primarily geared towards making the exchange more fluid by encouraging responsiveness and precision when setting up the transaction online, and punctuality and efficiency when completing the exchange. They are also intended to build mutual trust and a spirit of friendliness and to help the participants adapt to their interlocutor: “Let’s just say we reassure each other a little bit. That is the way it has always been – pretty friendly and polite,” says 32-year-old banker Julien, a Drivy user.

Consumers also give each other asymmetric roles in collaborative exchanges. The provider has primary responsibility for the smooth running of the transaction. The stance taken by drivers on BlaBlaCar typifies that responsibility: most providers never let anyone else take the wheel. Drivers even assume responsibility for the friendliness of the exchange: they make conversation and deal with passengers who are late in consultation with those who arrive on time. In the world of collaborative consumption, the recipient is not always right. He/she makes do with what is offered, particularly when it is being offered free of charge. Jean-Marc, a 41-year-old policeman who has been a recipient of items donated via Co-Recyclage, puts it clearly: “When you’re the one that wants something, you go and pick it up, at whatever time the other person decides. It’s as simple as that.”

Despite all these efforts at collaboration, such exchanges are not always especially friendly. Recipients are primarily struck by the lack of consideration they are sometimes shown: they complain of drivers “downing Red Bulls” and cramming in their passengers with suitcases in their laps, or donors who do not even take the time to dust off the items they are getting rid of. However, the mistakes that strike participants are not necessarily the most common ones. A lack of rigour in providers’ management of their online offering is a much more frequent occurrence. It is a fault some are willing to forgive, in view of the fact that the provider is not a professional, but others find it highly irritating to waste time waiting for offers that are actually no longer open.

Providers, for their part, complain above all about recipients wasting their time: the time cost of their involvement in collaborative consumption is a major factor for providers. They criticise recipients who ask questions to which they could find the answers on the site, who take too long to conclude the transaction, and who do not respond quickly.

Secondly, they are irritated by the fact that some people try to negotiate the product or service offered. Virginie, a 58-year-old secretary, complaints about the negotiation attempts of the purchasers with whom she is in contact on Videdressing: “We are no clearance sale, for goodness’ sake!“. 41-year-old salesman David, meanwhile, wryly recalls the renter who wanted him to bring his car to him at the airport: “Right, so you want me to waste a whole day to rent you a car?“. It is noticeable that no user complained about providers giving different treatment to different recipients. Just as the provider is free to choose his/her partner, he/she has the right to be more or less accommodating depending on his/her impressions of the recipient – a degree of flexibility not found in a normal commercial B2C transaction. The collaborative interaction remains, at heart, an interpersonal interaction between private individuals. And the sociability that develops within it is aimed, above all, at helping the exchange go smoothly.

Self-revelation

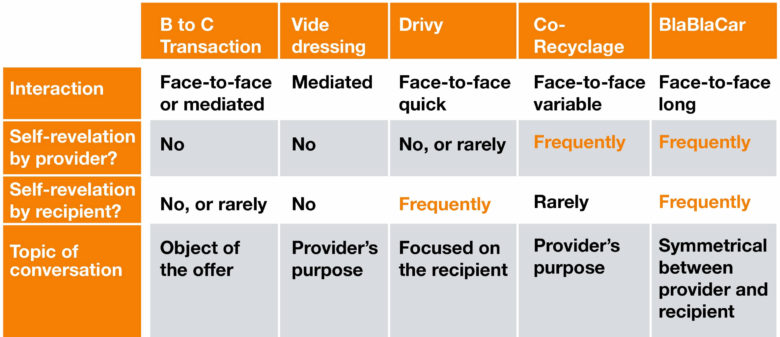

Analysis of the interviewees’ comments allows us to determine: 1) how the partners involved in a collaborative transaction are perceived; and 2) whether there is a difference in how people are described from one platform to another. The major difference between collaborative interactions and professional commercial relations is the extent to which the provider reveals him/herself during the transaction. Such self-revelation does not take place on all the sites studied.

The role of sociability in collaborative exchanges

The transaction on Videdressing is the closest to a typical exchange between a customer and a professional salesperson, leaving both parties unknown and on equal terms. All the buyers know about the sellers is their products, and the sellers do not know who they are selling to. At the very most, they might categorise “customers” by their behaviour: the annoying ones, the nice ones, etc. On Drivy, the meetings that take place about the rented car are all the faster for taking place in the street. The renters explain why they need the car, more than they would if they were renting from a professional, in order to reassure the owners. Indeed, they may even give some information about their personal lives. Providers reveal less about themselves than recipients, and the renters don’t know much about them. The way in which 62-year-old trainer Jacques describes the last owner from whom he borrowed a car is typical: “He was quite a young guy, maybe in his early thirties. I don’t know. (…) We talked about the journeys, about what I was doing and why I needed the car, etc. We talked more about me than we did about him.“.

Unlike these first two platforms, transactions on Co- Recyclage and BlaBlaCar enable providers to reveal information about themselves in a way that departs from standard professional practice. On Co-Recyclage, the nature of the interactions described varies considerably. People are chattier when the exchanges take place at the givers’ home (donations of furniture) rather than in the street (small items, clothes). Unlike with Drivy, the providers are often the ones who reveal the most about themselves, while the recipients may be reticent to disclose their reasons for resorting to donated goods. On BlaBlaCar, the interactions are described as being highly ritualised, with set milestones (initial contact, placings in the car, etc.) and classic conversation starters: “People often start by talking about car sharing. After that, we talk about more personal stuff. There is always a moment where everyone introduces themselves” (Carine, 29, journalist). Not always, but often, people experience a kind of intimacy with strangers. They describe two rewarding aspects of this experience: the surprise of coming across people with whom they “have lots in common” (homophily) or, in contrast, the surprise of meeting and talking with people who they “would otherwise never have met” (otherness). However, these encounters barely last beyond the time it takes to complete the transaction.

Fleeting encounters, but a rich and rewarding experience

While they enjoy the encounters and say they are happy to open up to other people, the users of the sites in question, particularly those who are in a couple, do not seek to build new relationships: “As an adult, it’s already hard enough to manage your relationship, your family, your close friends. If you spread yourself too thin, things get complicated.“. (Fanny, 29, HR specialist, currently looking for a job). A minority express a desire to identify partners purely for the purposes of collaborative exchanges or to expand their professional network. On BlaBlaCar, the instrumentalisation of the encounters is not taboo: for many drivers, having passengers is a way of making money, but also serves to pass the time and avoid tiredness. As 21-year-old student Noémie puts it: “Even if they are people you’re not necessarily going to stay in touch with, it’s always nicer and the time goes much quicker if you talk and exchange.“. It is rare for relationships to go any further than the original meeting.

With the exception of Videdressing, we found that all the platforms are conducive to enjoyable encounters enhanced by self-revelation. It may be that a romantic relationship, or a friendship in the broadest sense (a tennis partner, a person seen several times for a drink, etc.) develops, but this had happened to no more than half a dozen of our interviewees.

As the work done on sociability explains well, taking a relationship out of the context in which it was formed is a rare process. It is also striking to note that the descriptions of the relationships formed through these platforms are characterised more strongly by mutual help rather than by interpersonal feelings. The story told by Thierry, a 74-year-old pensioner who donates items on Co-Recyclage, provides a good description of how such bonds are formed: “One day, I was giving away back issues of Opera International magazine. A lady was waiting for me downstairs and she began to talk to me about music. She talked and talked… Then she said, “I don’t suppose you fancy a drink, do you?” Since then, we’ve been inseparable. When I have a spare invitation to something, I invite her. She gave me the details of her cleaning lady. That creates a bit of a social bond, which is nice.“.

This «bit of a social bond» remains central to the experience of collaborative consumption users. This experience has a positive effect on the way consumers perceive the strangers they are likely to meet. In this sense, it has a richness that simply cannot be gauged by the forging of a lasting emotional connection.

Habitual users of collaborative consumption do not seek to form new ties during the transactions they carry out. In contrast, the social experience they go through at the time of the exchange is often one of the things they like most about a practice which remains, above all, dictated by economic considerations. The market relationship between consumers cannot be directly equated to that between professionals and consumers. However, one lesson we might learn from studying this relationship is the need to take greater account of the interpersonal dimensions of the interactions that punctuate the customer path. The example of collaborative consumption suggests that we should encourage – among our customers and even between customers and professionals – reversible mutual assistance, fleeting exchanges and sharing of experiences.