ShaREvolution was conceived as a joint exploration of the present and future of collaborative consumption, a trend which has been thriving since the mid-2000s, but which also raises a number of questions. City councils are suing AirBnB; taxis are denouncing private car rent services such as Uber and car sharing for short journeys; the tax authorities are looking into web users’ undeclared income, etc. Will collaborative consumption remain a niche, or will it become a new economic paradigm. And if so, how?

Using the “Expeditions” format promoted by Fing, the project brought together public and private partners (real estate and telecommunications players; energy firms; carmakers; regional authorities; La Poste, the French Post Office; and Ademe, the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) as well as a varied community of contributors, including collaborative consumption entrepreneurs and users and stakeholders in the social economy.

The initial phase of the project made it possible to identify and map a number of the central issues and tensions surrounding the subject. A more detailed study landscape was then conducted, through case studies of its major players, together with a series of usage scenarios. Before thinking up any avenues for innovation, it seemed sensible to broaden our horizons by use of «extreme scenarios»: what new challenges, uncertainties and tensions emerge when we take certain trends and weak signals to extremes? This work, provided a good deal of material for the final report, which sets out new knowledge (offer, usage practices, trends), as well as hitherto untried ideas for innovation for businesses, public bodies, collaborative consumption players and citizens.

What does collaborative consumption cover?

In France and elsewhere in the world, there is still no firm and commonly accepted definition of collaborative consumption. ShaRevolution adopted the popular definition proposed by Rachel Botsman. However, we changed the scope to tailor it to the realities of collaborative consumption in France, focusing on peerto- peer exchanges and thus excluding certain aspects of the B2C economy of functionality, such as Autolib and Vélib’ (self-service car and bike schemes), incorporating both digital and non-digital practices, as well as some local exchange systems (e.g. La Louve).

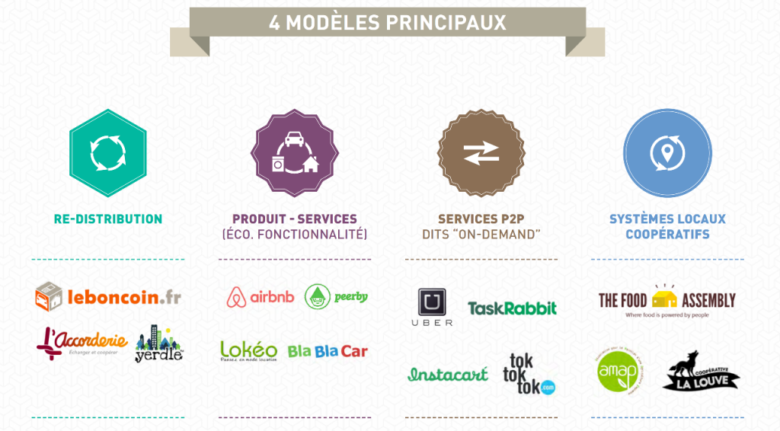

The collaborative consumption landscape on which we focused covers various cooperation models, built around the redistribution of goods, the economy of functionality (product service systems), peer-to-peer (P2P) services and local systems. Finally, we identified four main forms of collaborative consumption (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Types of collaborative consumption

Redistribution markets organise the transfer of ownership of an asset (or its “reuse”), be it through resale, exchange or donation, generally through a digital platform. This is the oldest collaborative consumption model and the one adopted by some of the great C2C pioneers, such as eBay and LeBonCoin, as well as a number of non-market transaction platforms such as Freecycle.

Product service system markets provide access to a physical resource (goods, vehicles, spaces) without any transfer of ownership. In short, they allow people to use an asset without having to purchase it. Examples include platforms for the P2P rental of cars (Drivy, Koolicar, etc.), apartments (Airbnb, etc.) and other items, as well as lending platforms such as Peerby and Sharevoisins.

Peer-to-peer on-demand services (P2P): individuals seeking a service are put in contact with other people who can provide it to them. The selection of services offered can range from classic car sharing (BlaBlaCar, IDVroom, etc.) to exchanging little everyday services (Instacart to get your shopping delivered, Taskrabbit for other tasks, etc.).

The last category identified is “cooperative local systems”: this category comprises a range of local practices based on cooperation between members of a network. The food sector features heavily here, be it through short food supply chains such as AMAP and La Ruche qui dit Oui !, through cooperative grocery stores or supermarkets, seed and product exchange networks, or through shared allotments. We have also included local exchange systems and other, hyper-local cooperative initiatives, such as cohousing, in this range of practices.

Business models vary here too: some use the tried and tested methods of the digital economy (subscription, freemium, advertising, commissions, etc.), with a particular penchant for payment by commission (service charges). This is the approach adopted by some of the best known collaborative consumption services (see Figure 2). Resale is another business model which is not too dissimilar (here, too, a commission is charged). It differs only in its organisational structure. For instance, Vestiaire Collective collects clothes that individuals want to sell, checks their condition, stores them and ships them to buyers. Digital and physical intermediation is essential.

Figure 2 – Collaborative consumption business/revenue models

This sketch highlights great diversity in the positioning and size of players, with market and non-market transactions coexisting side by side, as well as an ability to organize exchanges at global and hyper local level alike, while maintaining a presence in different countries.

The emergence of these new players in the economic landscape is proving disruptive for many established businesses and poses a number of questions: how will the landscape develop? What structure will it adopt? Will we see new monopolies emerge, as the growth of «unicorns» of the collaborative economy like Airbnb and BlaBlaCar might suggest, or will we move towards more distributed ecosystems? How will the scope of collaborative consumption change? And how will players from the «traditional» economy react and position themselves in relation to the collaborative economy if the latter continues to grow?

Collaborative consumption: a diverse range of users

The ShaREvolution project also looked at collaborative consumption practices, carrying out a study involving nearly 2000 users: the survey « Je partage ! Et vous ? » [I share! Do you?] was carried out online in the summer and early autumn of 2014.

There are a range of motivations in play – a desire to access new or alternative services, a desire to generate income, and a pursuit of meaningful consumption and new forms of sociability, among others. These, together with the diverse profiles and practices of collaborative consumers highlighted by this work and confirmed by a vast study by the French Directorate-General for Businesses (DGE), raise questions about the future of the sector. How can the needs of those seeking quality of service (convenience, speed and cost) be met without sacrificing the features that make the collaborative experience what it is? What status, rights and guarantees will be accorded to the new contributors to collaborative consumption, who put their belongings up for rent and offer their services? How can we prevent these new forms of consumption from excluding people – for example, those who do not necessarily have resources to offer or the means to promote them online (code, languages, etc.)?

Collaborative consumption: avenues for future development

ShaREvolution suggest four avenues for innovation in the field of collaborative consumption.

The first concerns the objects whose use can be shared via such platforms. If these practices continue to develop, those objects could be designed to meet the needs of sharing practices, combining robustness, security and reliability, with a form of intelligence to facilitate the object’s circulation.

By the same token, places could be designed to facilitate the storage and circulation of goods, stimulate exchanges and equip local collective projects. This is the subject of the second potential avenue for innovation.

The third focuses on the potential of collaborative consumption in terms of collective value. Collaborative consumption could complement the answers to social challenges already provided by existing players, particularly in the social economy. We have also explored the possible benefits of this avenue for a young audience, by considering how collaborative consumption could revitalise student policies and services by enabling students to experience what a collaborative campus would entail.

The final avenue, which we will consider at some length, concerns a crucial subject: forms of governance. It sprang from the observation that the development of collaborative consumption players often results in oligopolies and a concentration of value which seem paradoxical or even contrary to collaborative principles.

The growth in some players’ business is generating transformations of the services offered, sometimes to the detriment of users. Many start-ups appear to be caught in a vicious cycle: their rapid development prompts them to turn to financiers who expect a quick return on their investment. Any start-up seeking to adopt a more participatory governance and management structure, in which value is more fairly shared between users and/or employees, quickly finds itself stymied by the inherent characteristics of the digital economy. So, if we want to keep the collaborative consumption ecosystem diverse over the long term, it would appear to be time to invent new structures for collaborative enterprises and new development trajectories. Can we find inspiration in more participatory governance models which place great emphasis on redistributing value among users? How can we foster and nurture such approaches to generate collaborative projects based on a variety of models? Now is the time to invent alternative means of support, operating approaches and financing solutions.

These avenues are all worthy of further exploration by players from all horizons. While collaborative consumption is no longer a niche, neither can it be seen as a new universally applicable paradigm. It is already affecting a number of sectors, but to varying extents, with different practices impacting on different proportions of the population. It is already causing disruption for established players and existing business models. It is transforming our consumption habits by empowering individuals to make their own choices. It is creating uncertainty, but it is also opening up new opportunities for private and public players as well as ordinary citizens.