Over the last decade, the environment has become a major political issue and a matter that requires action from all business sectors. For several years, the digital sector’s impact on the environment has been closely scrutinized – reports have been published, action plans drawn up and commitments made by stakeholders. Calculating digital technology’s environmental footprint lies at the very heart of this debate and plays an essential role in quantifying the sector’s share, influencing stakeholders’ decisions and measuring the effects of the resulting actions. However, developing a means of calculating this footprint has proved to be difficult, resulting in differing methods, debates and controversy. How can these differences be explained? How is digital technology’s environmental footprint calculated? Who produces these figures? How do they come into the public eye?

Calculating digital technology’s environmental footprint is still a wide-open space and a field of investigation in its own right.

This exploratory study examines these questions by going back to the sources of the figures used to calculate the digital world’s environmental footprint. It uses and examines three corpora: articles on the subject in the French-speaking press between 2000 and 2021; 32 reports published by think tanks such as The Shift Project and Green IT, and institutions, including ADEME (Agence de l’environnement et de la maîtrise de l’énergie—the French Environment and Energy Management Agency) and the French Senate, between 2011 and 2021; and 20 reference articles from academic literature, which were analyzed in detail.

This study shows that measuring the digital world’s environmental footprint is still a complicated endeavor. In terms of metrics, a fixed and unified means of measuring this footprint and thus informing the debate is yet to be found. Measuring carbon is often a reference point in the search for a unified methodology, but it is far from conclusive. On the measurement front, scientists are not the only people producing figures—think tanks, institutions and industrial players are also involved in the debate. While this range of participants demonstrates a pledge of collective interest in the environment, it could also cause more division and hinder progress.

Discussion of the Digital World’s Environmental Footprint in the Public Sphere

Analyzing the press, we can see that digital technology’s environmental footprint has only relatively recently come into the public sphere. It only emerged in 2017 and didn’t see any real growth until after 2019.

Analysis of thematic groups of articles reveals that this increased awareness of the digital environmental footprint is linked to specific events. Classifying the subjects reveals four main thematic groups:

- A set of topics focused on pollution issues—one side focused on usage, the other on production;

- A set of topics regarding regulatory issues and challenges for economic stakeholders, which was not particularly prominent in the general press but appeared regularly in the specialized press (sectoral and professional);

- A very rare, yet very coherent set of topics relating to 5G;

- A final thematic cluster linked to political and social issues, characterized by the description of forms of protest, environmental action and political debates.

We observed three key ways in which the issue is brought to the public’s attention. The first way is through reports, which have a real focusing effect; their publication is repeatedly covered in the general or specialized press, especially since their authors, particularly in the case of think tanks, are making conscious efforts to distribute them widely. In addition, these reports establish a pool of sources and specialists that are subsequently cited, independently of their publications, via references, quotes and interviews when issues regarding the environment and digital technology come up in the news in other ways.

A second way the public is made aware of digital technology’s environmental footprint is through political debates on the environment. This was the case during France’s Citizens Convention for the Climate (2019–2020) and during the debate on France’s 2021 Climate and Resilience bill. In cases like these, the subject is covered more extensively in the general press.

The third way digital technology’s environmental footprint is brought to light is linked to public protests and movements, which was particularly evident during the controversy surrounding the rollout of 5G.

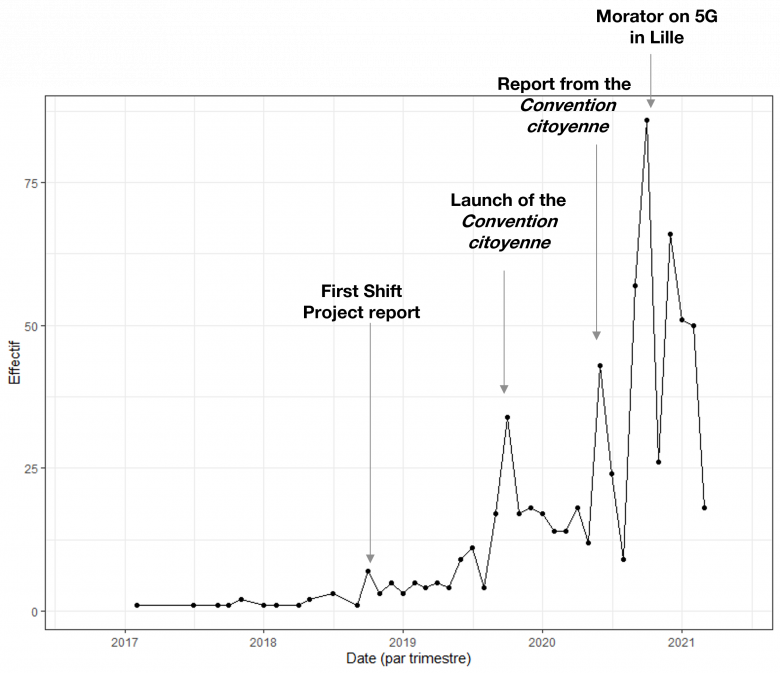

These three pathways to the public consciousness do not result in the same media coverage. When current events are projected onto the number of articles regarding digital technology’s environmental footprint over time (Figure 1), we can see that publication peaks are linked more to political events (the Citizens Convention, 5G) than to reports on the subject, which instead serve as a backdrop to the issue.

Figure 1. Number of articles on digital technology’s environmental footprint from 2017 to 2021

To support their statements, press articles rely on a limited number of seemingly key sources: two environmental think tanks (The Shift Project and Green IT) and three French institutions (ADEME; Arcep, the French agency in charge of regulating telecommunications, and the French Senate). The numerical evaluations in public reports feed the public debate and are considered by the press as a reliable and legitimate pool of information from which they can draw directories of metrics validated by scientific methods.

The Stakeholders Behind the Figures

These two think tanks and three institutions are what could be called “stakeholders in the field”—they endeavor to either produce or summarize figures regarding digital technology’s environmental footprint within a political context. The Green IT (2004) think tank, founded and led by Frédéric Bordage, focuses on digital issues and sustainable development, while The Shift Project (2010) is a climate change think tank chaired by Jean-Marc Jancovici. As for the institutions, ADEME has long played a pioneering role in environmental issues, and since 2020, other French institutions (Arcep, CNNum, the Senate and the High Council for Climate) have been producing detailed reports and roadmaps on digital and climate issues.

Academia is the other major area seeking to quantify digital technology’s environmental footprint. The first studies on the energy footprint of office technologies (Koomey et al., 1995, 1996) and personal computers were published in the 1990s. Between 1999 and 2000, the first debate took place over the Internet’s footprint (Mills vs. Koomey), then, between 2002 and 2005, the first efforts to reduce data center energy consumption began. In 2008, a first estimate of the energy consumption of Internet data transmission was produced (Taylor and Koomey, 2008). It was in the 2010s that the field really took off, with an increasing number of attempts to reduce the footprint of data centers, networks and information and communication technologies (ICT) in general. Today, the academic field is structured around three main pillars: laboratories in the United States (Lawrence Berkeley Lab, Koomey Lab, Stanford University and Northwestern University), European university laboratories (Zurich, Leuven, Dresden, INSEAD and VTT) and industry research centers (Huawei Tech Sweden, Ericsson and Sony).

Similarities and Differences in Measuring Digital Technology’s Environmental Footprint

A number of similarities exist in the methods used to measure digital technology’s environmental footprint. Firstly, two agreed-upon indicators are used: electricity consumption, expressed in kWh (kilowatt per hour), and carbon footprint, expressed in tons of Carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). These metrics echo the choices of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), which uses the CO2e metric, which can measure all forms of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by converting them to the equivalent amount of CO2.

However, many other metrics also exist, which are sometimes mentioned but rarely used. They fall into two very different categories. On the one side, there are specialized metrics that aim to report on the broadest possible range of impacts beyond GHGs: respiratory effects, acidification potential of land and water, depletion of mineral and fossil fuel resources, hydrological footprints and the masses of raw materials used. These metrics remain confined to limited and expert discussion circles. On the other side, there are non-specialized metrics that aim to make digital technology’s environmental footprint clearer by converting measurements to easily understandable data (hours of use, km of cables, number of devices per individual, etc.) or by using equivalents (duration of a light bulb being on, km by car, etc.). ADEME frequently uses the bulb analogy, while Netflix used the km equivalent to argue that streaming has very little impact. Specialized metrics endeavor to quantify digital technology’s environmental footprint more precisely, whereas non-specialized metrics seek to raise awareness and change behaviors.

There are also differences in how digital technology’s environmental footprint is measured, which are mainly related to the ways in which these figures are produced. A first point of divergence regards the measurement methodology. There are two different approaches. The first is the top-down approach, which takes the macro measurements of the energy consumption of a sector, system or stakeholder and weights or extrapolates them to measure the impact of smaller elements. The second is the bottom-up approach, which uses the footprint of devices, components, networks, etc., to calculate overall consumption. The two methods do not always produce the same figures.

The second point of divergence is that the scope of what is measured varies greatly from one study to another. Some studies seek to incorporate all digital technology, while others focus on a subsection: a part of the distribution chain, a business, a practice, a country, etc. What’s more, in global approaches, the definition of what constitutes digital technology often changes. It is agreed that devices (PCs, smartphones, tablets) that access online services (including access networks and data centers) are at the heart of digital technology, but extending the meaning of digital technology to connected objects (cars, IoT, consumer electronics) and specific connected practices (such as remote working) is subject to debate and difficult to take into account. Measuring therefore constitutes making decisions, separating practices and players’ networks—choices that will determine responsibilities in the impact of digital technology on the environment.

The third point of divergence is the assumptions used in the models. The measurements are based on the combination of a large number of estimates relating to the types of content consumed, the lifespan of equipment, its energy efficiency, the access networks used, the energy mix, etc. To run these models, various sources need to be used and such sources are sometimes neither accessible nor recent, which results in a significant amount of uncertainty.

Two Ways of Dealing with Uncertainty

Should we be surprised by such divergences? Why are they problematic? The differences in the methods for handling these uncertainties are particularly striking. Very broadly, academic circles devote a large amount of their attention to explaining and trying to solve them. This is at the heart of the scientific approach, which seeks to debate the various works and to create a cumulative and unified body of knowledge. Think tanks and institutions have a more ambivalent relationship with figures. They do not deny that calculating digital technology’s environmental footprint is challenging and some, such as ADEME and The Shift Project, take great efforts to explain their methods and share their models. However, they also want these figures to be accessible to the public and to fuel political debate and decision-making, which means setting aside doubt. For example, in 2020, French telecommunications regulator Arcep produced a breakdown of digital technology’s environmental footprint from networks and transport (see figure below). Within this breakdown, networks only account for 5% of digital technology’s environmental footprint, compared to 81% for devices. Such a depiction focuses on the manufacture and replacement of user devices, avoiding, for example, the systemic effects of the renewal of mobile network equipment due to new generations of networks.

Source: Arcep, Achieving Digital Sustainability, 2020

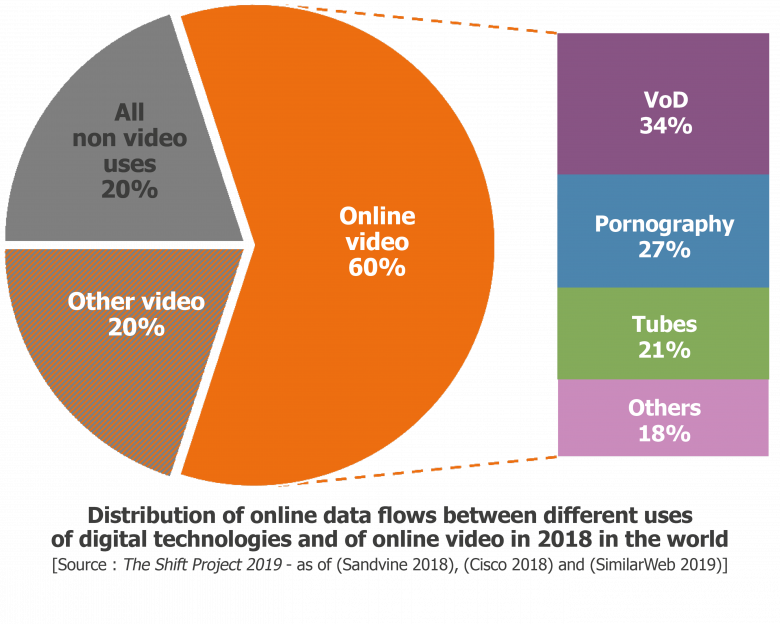

Similarly, The Shift Project highlights the significance of online videos, a subject to which it devoted a specific report in 2019: “The Unsustainable Use of Online Video.” The study focuses on data traffic and itemizes certain types of content that particularly contribute to the footprint, highlighting pornography as the second largest consumer (27%), adding environmental shame to moral stigma. This traffic-based approach minimizes the environmental impact of devices and creates a genuine moral debate on legitimate and illegitimate uses of technology in the face of the climate emergency.

Source: The Shift Project, “Climate Crisis: The Unsustainable Use of Online Video,” 2019

In both cases, these organizations play a decisive role in bringing the figures into the political eye. Even if the figures are simplified, the most important thing is that they are fed into the debate.

Measurement Sharing and Debates

Despite these differences in the use of figures, academic circles, think tanks and institutions are strongly linked when producing and utilizing figures relating to digital technology’s environmental footprint. Firstly, academic publications are an essential source of data and methodology for think tanks and institutions, even if the latter two cite their sources in different ways. Institutions cite little scientific work and refer more to think tanks; the think tank Green IT cites no sources or research work, while The Shift Project uses some academic work, without producing an exhaustive literature review.

The dispute over video’s impact is a good example of the overlap in circles and spaces of debate formed between academic experts, institutional experts and those working within think tanks. In 2018, The Shift Project combined scientific literature and commercial data to create a projection model to calculate digital technology’s footprint. The “1byte model,” presented in the Lean ICT — Towards digital sobriety report (2018), estimates the “average” footprint of one gigabyte (GB) of data by weighting the existing estimates for different technical configurations.

By adding complementary sources, this 1byte model was reused in 2019 to produce a specific estimate of the impact of watching online videos (Climate Crisis: The Unsustainable Use of Online Video), which led to the conclusion that online video viewing “generated more than 300 MtCO2e during 2018,” which is “comparable to the annual emissions of Spain,” or nearly “1% of global emissions,” or that 30 minutes of Netflix is equivalent to driving four miles.

By using alternative academic sources and other data, G. Kamiya, an analyst at the IEA (International Energy Agency), disputes this result and proposes an estimate of online video’s footprint that is 80 times lower, concluding that due to different countries using electricity from lower- or higher-carbon sources, 30 minutes of Netflix is equivalent to driving 100 meters in the United States and 10 meters in France (IEA, 12/2020). Such a significant difference has stirred up a debate that continues to grow, especially in academic circles. For example, the issue was discussed at Sweden’s Science & Society Forum (Nov. 2020, see video), where leading researchers from the field took part in the debate. J. Malmodin, trained at the Lawrence Berkeley Lab and now researcher at Ericsson Research, did not hesitate to publicly denounce The Shift Project’s estimates (“sorry, you got the wrong number…”), while A. Andrae, a researcher at Huawei, denounced Kamiya’s optimistic figures regarding Chinese data centers.

Challenged by such bad press about their business activities, stakeholders in the video industry are also involved in calculating their impact. The French TV channel Canal+ commissioned Greenspector to estimate the impact of watching one hour of video, live or on catch-up, on Canal+ interfaces (Greenspector, 12/2020). Greenspector produced an exhaustive study detailing its methodology and results. Greenspector falls between The Shift Project and the IEA in the debate, believing that “it is clear (and shared by the IEA) that the Shift Project study overestimates network consumption.” Netflix itself claims that one hour of video streaming emits less than 100 gCO2e, or “driving a gas-powered vehicle a quarter mile or 400 meters” (Netflix, 06/2021).

Finally, these discussions have found their way into the press, whether specific to video (for example: “We finally know how bad for the environment your Netflix habit is,” Wired UK, 03/2021) or a more general assessment of digital technology’s impact (for example: “Pourquoi le numérique contribue de plus en plus au réchauffement climatique” [Why digital technology is contributing more and more to global warming], Le Monde, 01/2022).

The controversy surrounding video shows how the debate is simultaneously unfolding in academic circles, corporate communication and the public sphere.

Conclusion: Stabilization Required in the Short-Term

In their executive summary on digital technology’s environmental footprint published in 2022, ADEME and Arcep highlighted that existing studies had “poorly harmonized methodologies, little transparency and only partially addressed the environmental impact of digital technology.” In terms of metrics, a fixed and unified means of measuring this footprint and thus informing the debate is yet to be found. Estimates differ according to the various fields and methods, as well as due to differing hypotheses regarding the development of networks and uses. The rapid pace at which infrastructure and devices are renewed makes this more complex. Measuring carbon is often a reference point in the search for a unified methodology, but it is far from conclusive. On the measurement front, scientists are not the only people producing figures—think tanks and institutions are also involved in the debate. Recently, industrial stakeholders have also taken an interest in the subject. While this range of participants demonstrates a pledge of collective interest in the environment, it could also cause more division and hinder progress.

Calculating digital technology’s environmental footprint is still a wide-open space and a field of investigation in its own right. Doubt should not be used as an excuse for inaction or for partisan purposes (such as the classic example of the tobacco industry). To inform debates regarding digital technology’s environmental footprint, three areas of focus have emerged:

- Opening up data: A significant part of the data used to measure digital technology’s environmental footprint is internal to companies in the sector. Openly sharing and documenting this data would play a significant part in reducing uncertainties.

- Bridging the gap between estimates: While academic circles and institutions focus on infrastructures and the long-term, the discourse and tools intended for the general public try to focus in on the impact of each individual use. Bringing together these two different means of measurement would be a key way to produce shared and unified tools.

Exploring alternative means of representing a network’s footprint: Beyond measuring carbon, we should concentrate on other environmental metrics, as well as investigate others linked to usage, which take into account the variety of behaviors and contexts, thus opening up other political dimensions of digital technology’s environmental footprint beyond input from industrial stakeholders or aggregated uses.