By diversifying the sources of production and consumption patterns of renewable energies and by encouraging local players to start producing, collective self-consumption seems promising: an increase in the amount of renewable energy available, improved synchronisation between production and consumption thus avoiding the problem of storage, regional deployment of agreed-upon infrastructure, better involvement of local players in managing the energy issue etc.

Collective self-consumption can offer more competitive prices than market prices, with a stable price outlook over 15 to 20 years.

What is collective self-consumption and how does it work?

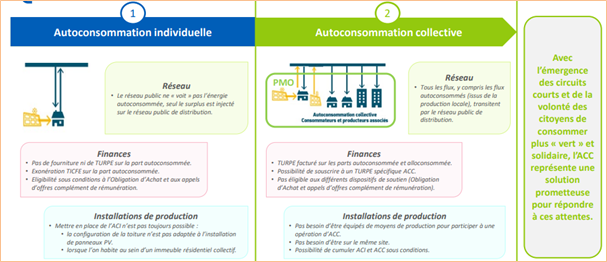

There are two different kinds of self-consumption — individual and collective.

With individual self-consumption, the producer is also the sole consumer, while with collective self-consumption, the electricity produced by one or more facilities is consumed by a group of companies, organisations or persons who agree among themselves to invest and set the price and distribution of the energy produced. The following diagram shows how this can look:

Comparison of individual and collective self-consumption — source: Enedis — Collective self-consumption 2021

In France, individual self-consumption is the most widespread of the two. It consists of a private individual or a company installing equipment to generate energy and consuming all or part of it. If any remains, it is generally injected into the Enedis grid.

In the French Energy Code[1], self-consumption is collective if “electricity is supplied by one or more producers to one or more end consumers”. Producers are legal entities (companies, local authorities — often a town hall) or natural persons who make their roof or land available for production equipment to be installed (usually solar panels). They may or may not be compensated for this. Consumers are those who enter into a power purchase agreement with the entity selling the electricity produced. This entity is called a “centrale villageoise” (local citizen-owned energy community) of energy production when individuals are involved in its governance and the project corresponds to the eponymous label.

A collective self-consumption project must be connected to the electricity grid in order to be able to distribute the energy produced to all the participating consumers.

There are three types of collective self-consumption projects depending on the players involved:

- Property projects, where producers and consumers are the same legal entity and electricity is therefore only shared between buildings belonging to the same property (town hall, schools, gymnasium, canteen etc.);

- Collective self-consumption is social when it brings together an HLM (Habitation à Loyer Modéré — low-income social housing in France) organisation with its tenants, and only its tenants;

- Open projects, where producers and consumers are different natural or legal persons. This is what a local energy community is all about.

In a collective self-consumption project, the existence of several producers and consumers and the regulations make it necessary to:

- Create the Enedis spokesperson legal framework: The organising legal entity whose role is to be responsible for the balance between the production of electricity and its local consumption in association with Enedis;

- Set a rule (called a distribution method) for allocating and billing the energy produced among the different consumers;

- Set a different price or prices for different consumer profiles (business, household, household in energy poverty etc.).

Collective self-consumption and individual self-consumption pave the way for decentralised power generation and consumption, thereby moving away from the historical centralised structuring of the energy market and its regulations.

Benefits and viability of collective self-consumption

A study conducted by Orange’s sociologists reveals that collective self-consumption can offer more competitive prices than market prices, with a stable price outlook over 15 to 20 years. The diversity of producer profiles—including public, private and cooperative entities—enhances the system. On the ground, developers of collective self-consumption are gradually overcoming legislative obstacles — regulation is rapidly evolving and long-standing players in electricity are resisting less and less. They are adapting collective self-consumption projects to fit a variety of consumers (individuals, businesses, industries, offices) to optimise the self-consumption rate and the financial viability of projects.

Challenges and possibilities

Access to land needed to install renewable energy infrastructure is becoming more and more competitive and expensive, increasing production costs. The relationship between those funding the investment in production facilities and the stakeholders directly influences the resale price of energy. In particular, the degree of (in)dependence of the organising legal entity, i.e. the entity behind the local project and the investment funders, can directly influence two decisive elements of the project: the distribution of energy produced among the project participants and the price level to which the participants will have access. In other words, if funders control the organising legal entity with a view to gaining a return on investment, the risk is that they will seek to maximise their earnings by setting a price level much higher than required to cover operating and management costs alone. However, new emerging players (Enercoop, Enogrid etc.) are offering specialised services to support the development of collective self-consumption by ensuring that collective objectives of low-cost and stable local decarbonised energy are respected in the long term.

On the consumer side

Collective self-consumption stakeholders are motivated in two ways — as citizens aware of ongoing climate change and as energy consumers. Therefore, participants in collective self-consumption projects are changing their habits without major difficulty by only running household appliances (water heater etc.) during the production hours of locally installed solar panels. However, the detailed analysis of their habits shows a lack of information on several factors that could influence their consumption decisions: the origin of actual electricity flows (among solar panels, wind, hydropower, nuclear or carbon sources) depending on the time of day, whether the consumption threshold is exceeded or not in relation to the drawing right defined by the collective self-consumption agreement, the actual usage of household appliances in terms of power and duration. Digital tools are still rudimentary and, in their current state, do not enable households to optimise or automate decision rules that would allow them to better achieve their main objective, which may be reducing their environmental impact, accessing cheaper energy, gaining resilience or ensuring that production is local.

Environmental and social impact

Although collective self-consumption does not necessarily provide any additional environmental value compared to non-collective projects, it boosts commitment to renewable energies. Consumers involved in collective self-consumption are motivated to change their energy habits, and digital technologies, although still emerging, support this transition. Collective self-consumption also promotes regional energy autonomy without compromising national solidarity, which remains the core value on which the national electricity grid was built. Two pricing rules apply to energy distributed under collective self-consumption: a uniform electricity transport price regardless of the distance travelled on the grid between the production site and the consumption site, and a uniform price of electricity consumed throughout the region.

Collective self-consumption: A solution for the future of the energy transition

Collective self-consumption is a major innovation in the energy landscape, offering decentralised and resilient renewable energy production thanks to the consolidation of small-scale, local solar power production. While requiring substantial upfront investments shared with stakeholders, this approach promises long-term benefits, particularly in terms of energy price stability and reduced dependence on fossil fuels.

[1] Article L315-2 of the French Energy Code